In two of his most outstanding Western flicks, Clint Eastwood manages to not only traverse the supernatural but also colorfully illustrate his growth as both a star and a filmmaker. In High Plains Drifter, he is a vengeful spirit looking to unleash the fires of hell itself. In Pale Rider, he is the embodiment of light, an angel of sorts sent by God himself to quell man’s insatiable greed. Structurally similar with subtle little differences, the two pictures are more than just the representation of the dichotomy between good and evil. It is two different chapters of the Eastwood history book, imbued with the spirit of an artist who chose to do things his way, while still trying to accentuate his quirks and idiosyncrasies.

‘High Plains Drifter’ & ‘Pale Rider’ Are Two Sides of the Same Coin

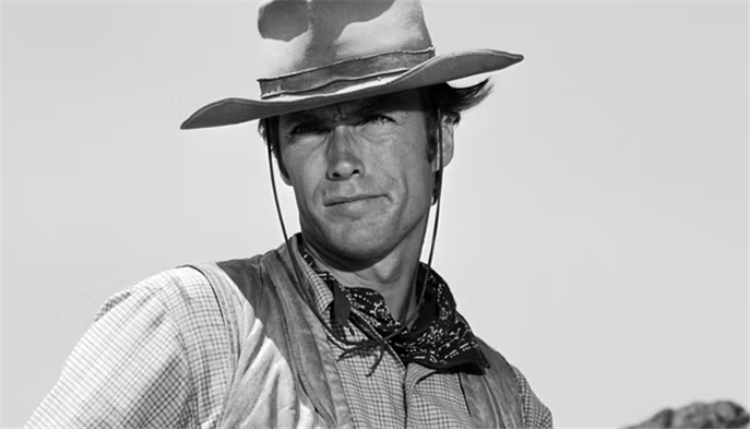

High Plains Drifter has Clint Eastwood as a wanderer riding with all the bravado in the world into the town of Lago. The townsfolk are helpless, and since he is a skilled marksman with no fear in his eyes, they ask the stranger to protect them from the impending return of three prisoners they have banished before. One by one, they accede to his ludicrous wishes while displaying the unforgiving indignation of a man who has lost everything. As it turns out, his moves are justified as he is assumed to be the reincarnated spirit of Jim Duncan, the marshall who was mercilessly murdered by the returning crooks while the entire town watched in indifference. Like the personification of death himself, the stranger eliminates the criminals brutally, and burns the entire town down, avenging himself in the process.

In a similar vein, Pale Rider has the icon appear as a miracle, borne out of a wish from one of the townsfolk terrorized by a mining company. There is gold hidden beneath the rocks of Carbon Valley, and Coy LaHood, the town’s mineral magnate is hell-bent on evicting the independent miners working day and night to reap its gifts. When the harassment gets out of hand, the mysterious preacher arrives and becomes their saving grace. Urging the miners to come together, he begins to put an end to their suffering by gunning down LaHood’s hired guns, restoring the peace. Both pictures end with Eastwood riding into the sunset under opposite circumstances.

Clint Eastwood’s Movies Don’t Always Please Critics

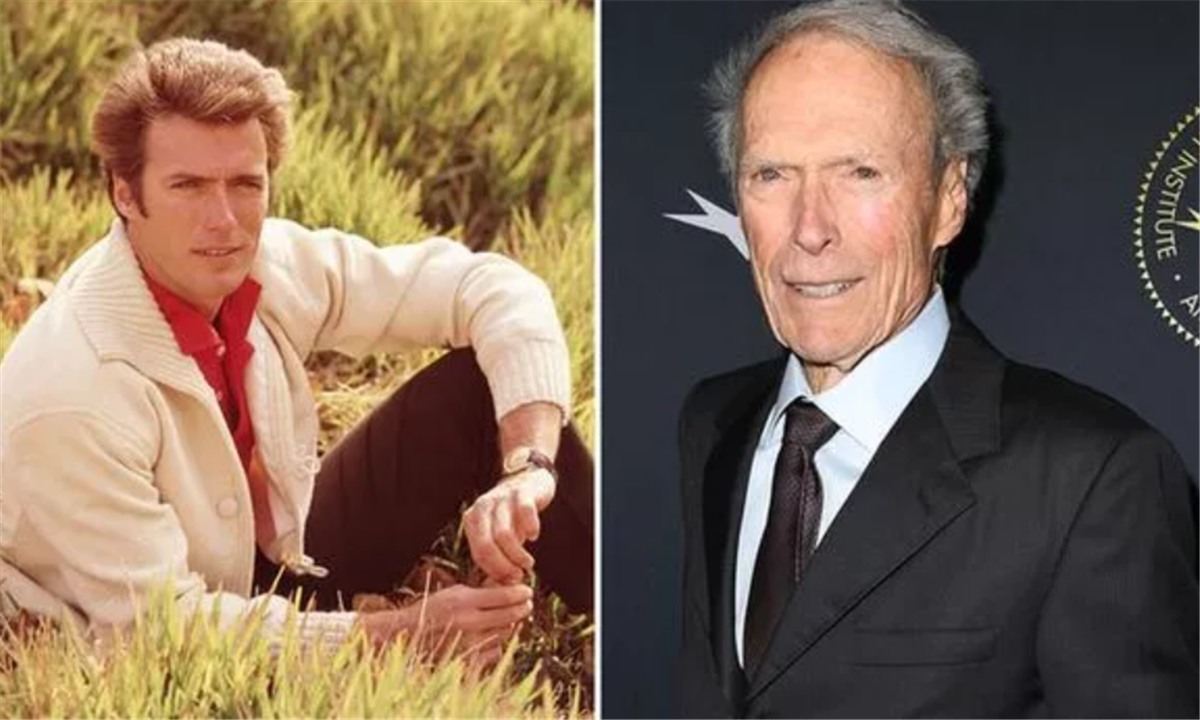

There is no doubt that Clint Eastwood is one of if not the biggest names not only in the Western genre but in American cinema as a whole. Interestingly enough, despite his status, he wasn’t always on the receiving end of acclaim. Some critics were dismissive of his one-dimensional acting, the political ideologies affiliated with his work, and an affinity with meaningless violence in the name of masculinity. Despite his success with Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy, the series of pictures was initially met with undeserved disapproval, at least in the Western world. His prospective characters were met with the same venom. At the forefront of this is the celebrated film critic Pauline Kael, and in her scathing commentary Dirty Harry: Saint Cop, espoused how the Eastwood film is full of immorality, and brimming with “fascist potential”. On the surface, Eastwood was very dismissive of Kael, calling it as a mere call for attention. However, some say that he took it personally, with his ex-girlfriend Sondra Locke mentioning in her autobiography that Eastwood had psychiatrists psychoanalyze Kael’s reviews.

Whatever the case may be, it is completely mistaken to reduce Clint Eastwood’s works into the adjectives so colorfully remarked by Pauline Kael. Upon examining his artistry, both as a star and as a filmmaker, it would appear that he is enamored with the human experience of violence and how they would respond to it. Yes, it could be said that his works are generally easy to understand, but being easy to understand does not equate to superficiality. You could even say that he used the Kael commentaries and the other negative assessments as fuel to the fire. This is most evident if you contextually look side-by-side at the two similar Westerns he made in different periods of his life.

With ‘Pale Rider,’ Clint Eastwood Reinvents Himself

One could easily surmise that High Plains Drifter is a direct response to the criticism of his ultra-violence and ability to only play the man with a cigarillo, or other versions of it. Naturally, the main character is a cigarillo-smoking stranger, who literally and figuratively paints the entire town red. Do they say he’s violent? Alright, so he whips his enemies to death and shows absolutely no mercy to the seemingly innocent residents of Lago. They say he has fascist tendencies? Okay, so the stranger becomes a dictator for the town, living like a king and instilling fear into their souls. Do they say he’s one-dimensional? Perhaps, and he shows little to no emotion in every minute of the picture. It is a feature brimming with nonchalance and contempt, brilliantly painted with the strokes of a filmmaker with a clear intention in mind: he does not care what you think of him, and he will do as he pleases. The result of this is a picture that makes us sympathize with an almost irredeemable character, and every second of it is simply enthralling.

As time went on, he began to be conscious and self-aware of how people viewed the Eastwood mythos and began to slowly and systematically destroy its figurative walls. In Magnum Force, Harry Callahan separates himself from a hypermasculine group of “fascist” cops and stands up for what he believes is the right way of life. In The Enforcer, he aligns himself with a female which enables him to be humanized. Every Which Way But Loose took things to a completely different level by having him and his image be literally and figuratively beat up. Most importantly, Escape from Alcatraz’s ending carries the most blatant and significant moment of removing the old vision of Eastwood. When Frank Morris removes his mask and escapes the prison, it is the cinematic representation of Clint Eastwood shedding his old persona, and venturing into a new world.

He may have jettisoned some of the marks of his legend, but to fully reinvent himself, he must go back to where it all began: the Western. This is where Pale Rider comes into play. Like the stranger in his earlier film, the preacher is also implied to be the resurrection of a man the protagonists knew before. It stands on the shoulders of his vicious early characters but subverts their qualities to come up with someone more principled and aligned with the general idea of righteousness. Here, the preacher’s violence is more purposeful. Yes, it is still the gun-slinging Eastwood that audiences have loved and critics have despised. Yet here he is, using his lightning-fast hands to fire upon the enemies of the everyday man. Even though he is celebrated as the de facto leader of the town, he dismisses a chase for power and selflessly encourages them to never lose hope. The fact that his main rallying cry is to get the miners to stand together to survive completely demolishes the notion of any sort of fascist tendency. The preacher may have finished off all the heavies, but the glory belongs to the people of Carbon Valley. It is in this picture where he begins to show a more sympathetic side, a side that will continue to be explored and subsequently subverted again, particularly in Unforgiven.

If you think about it, there are a lot of things about these two pictures that turn things on its head. You have a cinema giant, who made his name in Westerns. He puts a supernatural spin to them, and simultaneously presents complete disregard and self-consciousness, all in the immortal image of the man with no name, riding a horse and drifting away to the sands of time. It is in High Plains Drifter and in Pale Rider where the clearest image of the evolution of his oeuvre is seen, both as a star and as a director. Akin to the reincarnated spirits of Marshall Jim Duncan and The Preacher, the Clint Eastwood image rises out of the dust like a Phoenix, borne out of the ashes of the man with no name.