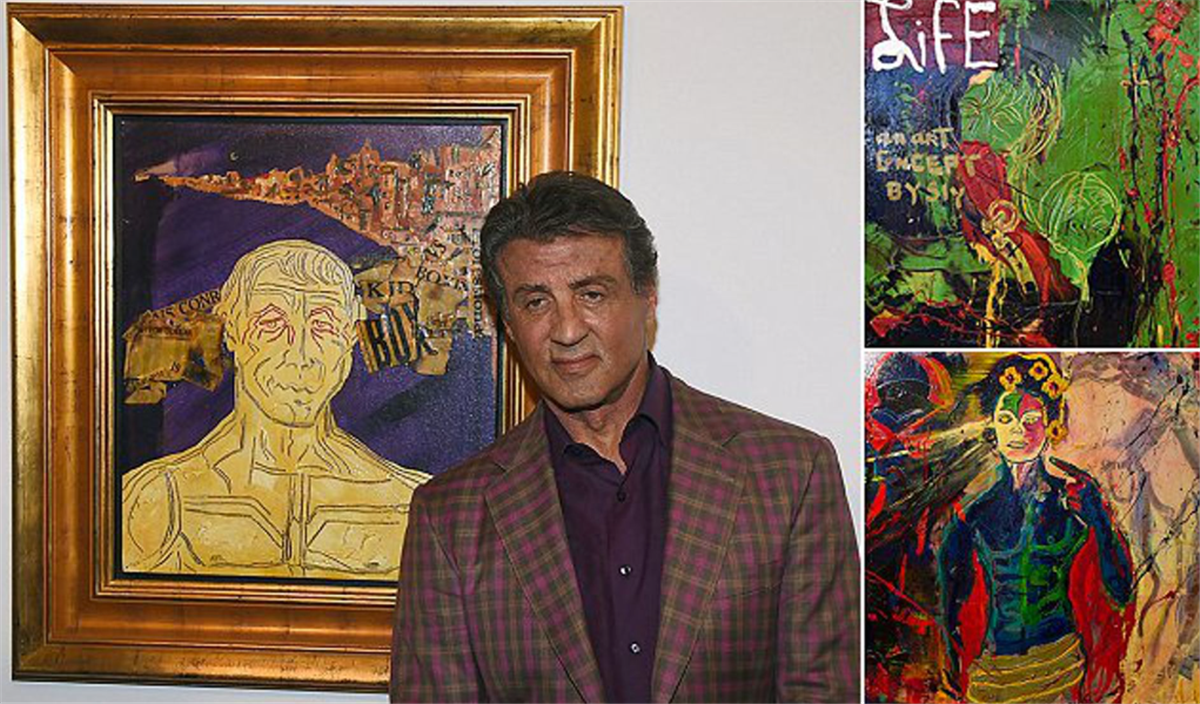

However you rate him as a visual artist, it is clear that Sylvester Stallone throws everything he’s got at his canvases: his heart, his soul, perhaps even the paint. Stallone estimates that he has produced between 300 and 400 works, starting with a portrait of a primitive man in a jungle painted when he was eight. “It was the first time and it seemed to come out of nowhere,” he recalls. “It just percolated in my mind.”

A new exhibition at the modern art museum in Nice, France, presents a retrospective of the 68-year-old actor’s more mature works, painted between 1975 and 2015: highlights selected from a little-known career that runs in parallel with his on-screen adventures as Rocky Balboa, John Rambo and a dozen other last-ditch action heroes. Most people, Stallone included, take his acting with a pinch of salt. Can we take him seriously as a painter? The commercial gallery director Mathias Rastorfer, a fan and advocate of Stallone’s works, thinks we should.

“When you hear about it for the first time, you think, ‘Ah yes, one of the Hollywood painters’,” he says. “So the whole point of a serious gallery showing someone like Sylvester Stallone was to show what’s possible in art, and to make this a serious endeavour and not a society endeavour. We avoided like the devil anything that would make this a Hollywood thing.”

This is hard to do. The press conference that marks the opening of Stallone’s exhibition is introduced by the mayor of Nice and attended by journalists from Britain, France, Germany, Switzerland and Japan. When the actor tours the gallery to pose for photographs, he is pursued by a maul of paparazzi.

During the Q&A, even the famously discerning French are not the slightest bit sniffy. To a man, they ask forelock-tugging questions about Stallone’s artistic endeavours as an actor, director and painter. He returns the compliment. “I have a great rapport with the French,” he tells them. “It’s odd, but it just seems very natural. If I were ever to learn a language for some reason, I think French would be the easiest.”

Like Rocky, most of Stallone’s paintings contain a restless, pent-up energy. His favourite colour is arterial red. (“Painting attacks the senses,” he says.) He likes to paint in his garage, sometimes wearing his pyjamas, occasionally naked. To make room, he first has to move his Aston Martin DBS, Mercedes-Benz SL65, Bentley Continental GTC and Porsche Panamera on to the front drive. Stallone works best when gripped by “crisis” and “emotional upheaval”. You believe him when he says that his biggest difficulty as an artist is knowing when to stop.

This new exhibition is a rare chance for members of the public to see Stallone’s work in the flesh, although he has previously exhibited at the Russian Museum in St Petersburg and at the Galerie Gmurzynska in St Moritz. Stallone has long been an enthusiastic art collector, at one time owning works by Claude Monet, Francis Bacon and Anselm Kiefer. Understandably, he refuses to sell Finding Rocky “at any price”, but other well-known private collectors have invested in his work. “Schwarzenegger has. Travolta has. People bought them early on,” Stallone says with a chuckle, “before they knew better.”

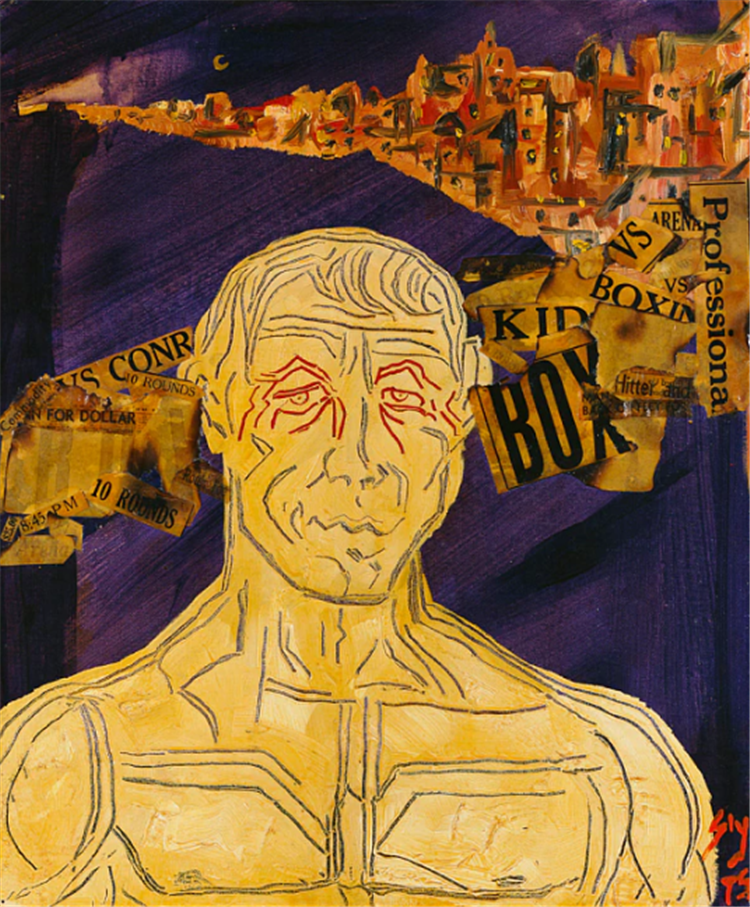

On Finding Rocky (1975)

“Usually I try to visualise something before I put it into words. Words are very difficult and sometimes unforgiving. So if I could see what Rocky looked like, then perhaps I could write about him. So I began to work on this image. But I didn’t want to use a brush because I felt that the character was made out of industrial tools. He was a man that was forged by the hardships of life. So I put this image up there and I started to actually carve it with a screwdriver. Then I took newspaper clippings which would reflect what it would be like to be a very poor, unsuccessful man, especially a boxer, and then, all of sudden, the image came alive. Then I said, ‘OK, this is a character I would like to see written about because he looked interesting visually.’ If he looked interesting visually, then I think that he would translate through to literature and then cinema. I know it sounds ambitious but that was the genesis of Rocky.”

On being painted by Andy Warhol

“I was in Studio 54 – I think it was 1979 or ‘80 – and Andy came up to me and introduced himself. He was very shy – and he started taking photos. He took them at very stealthy angles: click, click, click, click, click. Then a year or so passes and I’m in Hungary filming Escape to Victory with Pelé and Michael Caine. At the weekend, I go down to the Cannes Film Festival, just to take a break, and there he is at the Hotel de Paris. Andy goes, ‘Sylvester, can I take a portrait?’ And I say, ‘Yes’ and take my shirt off. At that point I’m very thin because I’m playing a goalie in a POW camp. So he takes probably the thinnest picture I’ve ever had taken of me since I made it. Then he sees me a year later at Studio 54. I now have a beard for Nighthawks and he goes, ‘I’ve got to do another portrait.’ I looked the complete opposite. That’s how we met and we just continued to cross paths. I got Andy, do you know what I mean? Talk about strange pairings but we just had a great rapport. But he never saw my art. I wasn’t going to brag about my art to Andy Warhol.”

On his use of incomplete frames

“If I put a frame around a tree, the tree is going to grow through the frame. Well, I think that a painting, the more you look at it, [the more it] takes on different impressions and interpretations. You can’t frame an emotion forever. It’s constantly being expanded or taking on a bigger myth. Some paintings have taken on such grand history. I don’t think you can hold in anything that’s artistic. You can’t freeze it in time. The [incomplete] frame is symbolic of just letting it grow. As Anselm Kiefer said, the art is in transition.”

On his recurring clock motif

“Early on in my life I realised that man is totally pressed upon by the sense of time racing. Everything is timed. So I started to put clocks on my images, usually the ones of actors – Marilyn Monroe, W C Fields, Errol Flynn. Now if you imagine their lives lasted 12 hours, I would paint them at 10, as opposed to what they looked like at four. At four they’d be youthful, vibrant, optimistic. But then you move ahead to the 10th or 11th hour and reality has set in. Life is not everything you thought it was going to be. The colours have become darker, the eyes more sunken.”