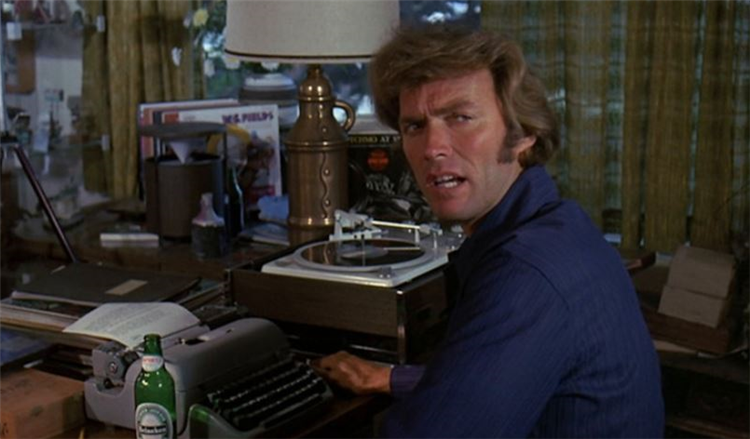

Regardless of their profession, everyone wants to know if they’re doing a good job and be praised for it if they are. However, enough actors and filmmakers have been so affected by reading reviews of their work that they’ve sworn off it altogether, but Clint Eastwood has always been famed for his hardened exterior.

The silver screen legend has been involved in numerous classics on either side of the camera, but just like every notable star and/or auteur with a career spanning decades, there have been more than a few stinkers along the way. Based on his no-nonsense persona, a critical drubbing should be water off a duck’s back for Eastwood, even if there are always exceptions to the rule.

As one of the most vaunted critics of her time, Pauline Kael’s opinion carried more weight than most, and it became abundantly clear that she wasn’t a huge fan of Eastwood’s work. His output very rarely received pass marks, and her disdain covered everything from the ultraviolent Dirty Harry saga to more quaint fare like Bird, which she actively despised.

Kael wasn’t a huge fan of Harry Callahan in general, but Eastwood took particular issue with her review of The Enforcer, the third entry in the series. In fact, it affected him so deeply that the four-time Academy Award winner’s then-partner Sondra Locke noted in her autobiography The Good, the Bad, and the Very Ugly: A Hollywood Journey that he’d enlisted a psychiatrist to try and get to the root of Kael’s problem with him.

Locke wrote that after Kael’s insight on The Enforcer had gone public, “Clint asked a psychiatrist to do an analysis of her from her reviews; it concluded that Kael was actually physically attracted to Clint, and because she couldn’t have him, she hated him. Therefore, it was some sort of vengeance, according to Clint.”

The antagonistic relationship between Eastwood and Kael was nothing if not strange, with the two regularly taking shots at each other across different mediums. That said, whereas the latter would keep it professional and give his films a critical thrashing, the former tended to make it a touch more personal, once describing her as an attention-seeker with a habit of “making a lot of outrageous statements not having any bearing on anything.”

Eastwood also suggested to Richard Shickel that Kael had reached out and confessed to giving him unfair treatment, going so far as to refer to herself as “just a dumpy little movie critic.” And yet, Locke maintained in her book that no such conversation ever took place, and the Hollywood legend had made the entire thing up, meaning that no formal – or official – apology was ever extended on the critic’s part.

Mounting psychoanalysis on Kael after she’d panned The Enforcer was a strange move on Eastwood’s part, even more so when the findings determined that the reason she showed so much hostility towards his work was that she had the hots for him. Most creatives would take a bad review on the chin and move on, but for whatever reason, Eastwood wanted to get to the root of Kael’s issue, even if the results he alleged to have been given basically amounted to playground behaviour.