When former Royal Marine Levon Cade (Jason Statham) is recruited to find his boss’s kidnapped daughter, our resistant hero mournfully declares: “It’s not who I am anymore.” But anyone who has been a fan of the action star over the last 25 years can predict that he will soon change his mind. A Working Man provides familiar, comforting pleasures as Statham churns out gruff line deliveries when he’s not killing, punching or stabbing anyone who gets in his way. Reteaming with director David Ayer (The Beekeeper), Statham barely breaks a sweat as he goes through the motions of this over-long, under-nourished action-thriller.

Over-the-top violence

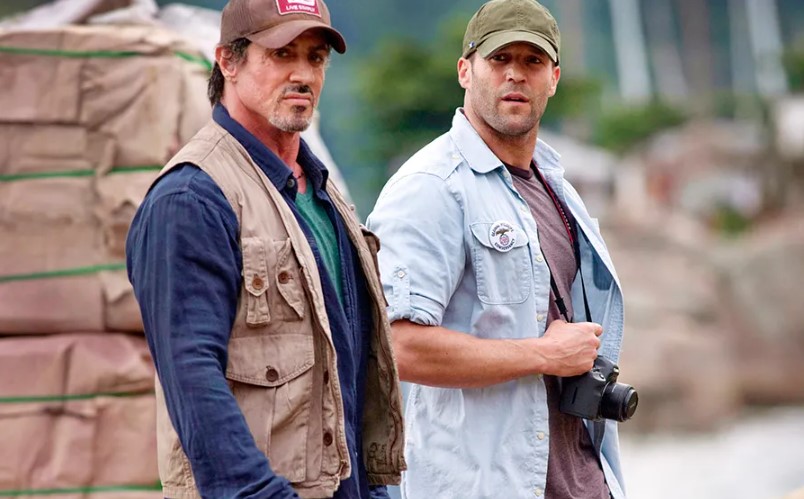

The Beekeeper collected $163 million worldwide against a modest budget, and A Working Man, which opens in the US and UK on March 28, features a similar commitment to down-and-dirty fight scenes and graphic violence. Statham is a draw, of course, but so is Sylvester Stallone, who doesn’t appear on camera but produced A Working Man as well as co-wrote the screenplay with Ayer. It’s based on the Chuck Dixon ‘Levon Cade’ series, with the central character now a Brit-in-exile (Stallone worked closely with Statham on The Expendables series).

After decades in the British military, Levon is now working in construction in Chicago. Still suffering from PTSD, Levon has put aside his violent past and is grateful to Joe (Michael Pena), the kindly head of this family-run company for giving him a chance at a new life. But Levon will have to reconnect with his past after Joe’s 19-year-old daughter Jenny (Arianna Rivas) is abducted by human traffickers — and he will stop at nothing to bring her home safely.

Initially, Ayer tries to humanise this pummelling film by introducing the demons that still visit Levon. (Unfortunately, those demons are fairly minor, and mostly expressed through occasional uncontrollable shaking in Levon’s hand.) Then when Russian gangsters kidnap Jenny, A Working Man attempts to offer moral indignation at the very real global scourge of human sex trafficking. But these stabs at emotional undercurrents hardly resonate — and the fact that Levon is partly disgusted at these criminals because he himself has a daughter only highlights the hamfisted dramatics.

Even in his late 50s, Statham casts a striking figure, with his shaved head and trademark scowl as imposing as ever. A Working Man lacks the outrageous stunts of his early star vehicles, but he’s still a commanding presence – few action stars are as effective at hinting at their physical prowess, creating a tension that is then released whenever he leaps into a fight scene. The stoic Levon opens up to only a few people — including his young daughter Merry (Isla Gie) and his fellow former soldier Gunny (David Harbour) — and Statham has a knack for revealing the softer side of his tough-guy characters. But when Levon starts his dogged pursuit of Jenny, he shows no mercy — especially during a lengthy finale that flaunts its over-the-top violence.

A Working Man’s villains, a collection of the blandest Russian-mob stereotypes imaginable, are fare less memorable. Levon’s investigation will see him sink deeper into the Chicago underworld, first encountering Kolisnyk (Jason Flemyng) and then seeking out the mobster’s screw-up son Dimi (Maximilian Osinski) and his sordid associates. Not one of these walking cliches is remotely memorable, however. Whereas Ayer’s best films, like 2012’s End Of Watch, crackle with a grubby authenticity, A Working Man’s lurid phoneyness undercuts the sense of outrage the disturbing subject matter is meant to evoke.

The film’s title refers to Levon’s working-class humility, his laudable desire to be nothing more than a good father to his child. (Another cliched narrative element is that Levon’s wife died and his disapproving father-in-law subsequently took custody of Merry, which creates a convenient reason to feel sympathy for our goodhearted hero.) In its more diverting moments, A Working Man echoes its no-fuss protagonist, executing compact action set pieces that eschew flashy CGI in favour of good-old-fashioned shootouts and hand-to-hand fighting. But that spareness too often belies the lack of ingenuity elsewhere.