Clint it’s worth celebrating the fact that this Hollywood legend is still turning out work at a faster clip and higher quality than practically anyone in the business. Granted, prolific doesn’t always mean better, and it can be frustrating to see his fans greet every new film as a fresh masterpiece, when only a fraction of them truly deserve the title. But consider that since the turn of the century, he has given us 17 films including “Mystic River,” “Million Dollar Baby,“ “Letters from Iwo Jima” and “American Sniper” (the latter earned more than half a billion dollars, baby).

Five decades ago this year, Eastwood made his directorial debut in “Play Misty for Me,” and for a time, he was dismissed as one of those “actors who directs” — a condescending label typically slapped on dilettantes who did the job just once, like Marlon Brando (with “One-Eyed Jacks”) or Steven Seagal (“On Deadly Ground”).

But here we are, with 39 movies made — that’s counting Clint’s “Cry Macho,” a grizzled-cowboy-makes-good saga in which he also appears — and the world has come around to recognizing Eastwood as a filmmaker first and an actor second. It helped that the French took him seriously, as press agent Pierre Rissient and other Paris-based champions insisted on treating Eastwood as an auteur early on. Five of Eastwood’s films have competed in Cannes, including “White Hunter Black Heart,” in which he played a loosely fictionalized version of John Huston, another “actor who directs” — and who did his best work behind the camera.

Like Huston, Eastwood can’t be pegged down to a single genre, having tried his hand at many, from action (you can feel Don Siegel’s influence in “Sudden Impact”), romance (“The Bridges of Madison County”), war (“The Flags of Our Fathers”), musical (“Jersey Boys”) and of course, Western. Apart from his “shoot first, ask questions later” Dirty Harry character — who appeared in five movies spanning the ’70s and ’80s — Eastwood is most associated with the Western, having effectively replaced the earlier tradition of a friendly, white-hat hero with a stoic, understated character of ambiguous intentions.

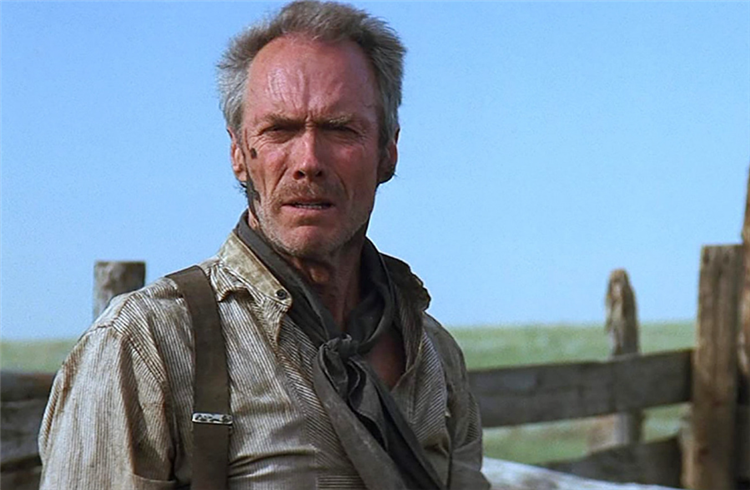

At 34, the actor already had crow’s feet when he shot “A Fistful of Dollars,” the 1964 spaghetti Western that effectively made him a star. The skin around Eastwood’s eyes creased like leather every time his Man With No Name squinted in that film, underscoring the fact that he wasn’t some twenty-something upstart catching a break, but a man whose rugged mug masked a certain life experience. Rugged yet handsome, since Eastwood’s undeniable beauty was a factor as well — and the very quality that “Dirty Harry” director Siegel leveraged in Civil War reverie “The Beguiled,” causing a house full of Southern ladies to swoon over this wounded Union Army stud.

Early on, Eastwood didn’t have the same power to choose projects that we see today — which might explain a seemingly daffy outlier like “Every Which Way but Loose,” though the orangutan buddy movie proved to be his biggest box office success, so it can’t have been all that terrible a decision. Overall, Eastwood has remarkably consistent in his choices, chiseling out one of the clearest and most iconic screen personas of his generation. It helps that he hardly ever appears in other director’s films (the last of those was back in 2012, appearing in Robert Lorenz’s “The Trouble With the Curve”), which further allowed him to shape his own brand. And even certain off-screen missteps — like the 2012 RNC convention bit where he addressed an empty chair — felt like a natural extension of the surly “Get off my lawn!” guy he’d been developing in movies.

Eastwood’s most enduring film as director and star, “Unforgiven,” makes especially keen use of the actor’s “baggage,” effectively deconstructing the image he’d cultivated over the duration of his career to date, reaching all the way back to his Rowdy Yates character on the “Rawhide” TV series. That more nuanced recasting of that eager enforcer role emerged in the trilogy Eastwood made with Sergio Leone, and grew grittier still in “High Plains Drifter” and “Pale Rider,” before finally being overturned altogether for “Unforgiven.” With that project, knowing we’d be rooting for him, Eastwood encouraged us to question the motives of revenge and the morality of those who use violence to solve problems.

Whereas Leone pushed his shooting style to self-aware extremes — dramatic angles, extreme close-ups and music cues that threaten to upstage the action — Eastwood has conspicuously resisted that tendency in his own approach. As both director and star, he embraces the “less is more” philosophy, such that his technique rarely calls attention to itself. He famously doesn’t indulge multiple takes or endless shooting days, committing to practically whatever performance his actors give — which works great when paired with professionals, but less successful when working with child actors (“Changeling”) or non-professionals

(“The 15:17 to Paris”). Nor is he fussy about the screenplays, which is a shame, since a handful of his best-loved movies could have been a whole lot better if their writers had invested more effort up front.

Personally, I’m partial to “A Perfect World,” the film that immediately followed “Unforgiven,” a 1960s-set crime movie with conscience, in which Kevin Costner’s escaped convict character takes a young Jehovah’s Witness hostage on a cross-country pursuit. And though it has its detractors, I consider “Mystic River” the best film Eastwood has made this century: a wrenching, noir-toned look at the American Dream turned upside-down. That movie, like the Dennis Lehane novel that inspired it, recognizes the enormous effort that working-class parents invest in creating a better life for their children even as it confronts the turmoil that ensues when someone breaks that chain of hope by hurting or killing a child. It’s Greek tragedy transposed to the streets of Boston.

So many filmmakers lose their touch past a certain age. That’s why Quentin Tarantino has pledged to call it quits after his 10th film, for fear that he can’t sustain the quality over time. But Eastwood ain’t going anywhere, like a gunslinger with a seemingly endless supply of ammunition, still shooting after all these years.