Clint Eastwood is cruising down Dolores Street in Carmel, Calif. looking for a place to park his understated silver 1978 Mercedes 6.9 sedan, a car as rare on American roads as snowfall on the nearby Monterey Peninsula. “This thing is all engine,” he’s saying about the 140-mph autobahn eater. “But people kind of think it’s an old man’s car.” A candy-apple-red Mustang pulls alongside. Eastwood’s head turns slowly toward it, and his face crinkles into that High Sierra smile that has flashed across movie screens for the better part of three decades now. Emboldened, one of the girls in the Mustang leans out the window and says, “We’d like to buy you a drink, sir.”

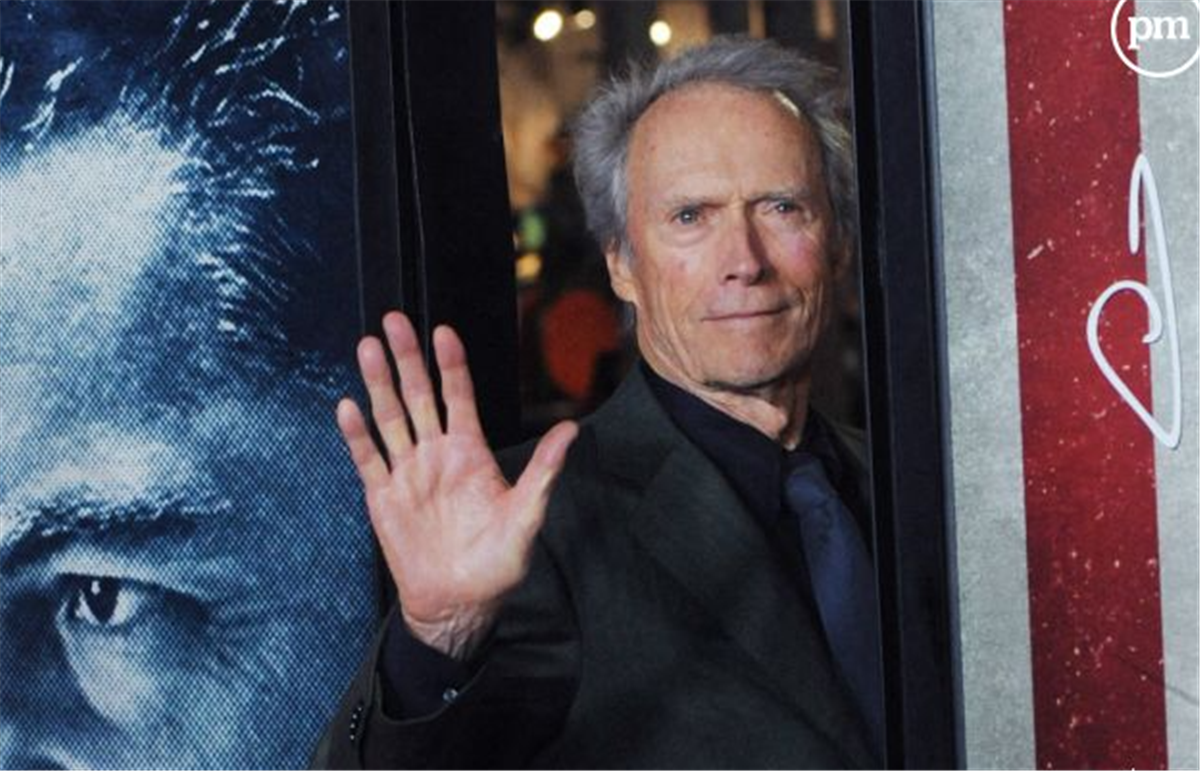

What’s this? Young women calling Clint Eastwood “sir”? Has it been that long since he was the aptly named Rowdy Yates of CBS’ Rawhide or the laconically virile “Man With No Name” in Sergio Leone’s 1960s spaghetti Westerns? But perhaps the young woman’s commentary on the passage of time was not nasty, just respectful. Those who would cluck at the sad plight of an aging star haven’t seen Clint lately. They should also remember this: The young ladies are still asking.

A short time later, surrounded by the regulars at the Redwood Bar of the Eastwood-owned Hog’s Breath Inn in Carmel, Clint complains about questions concerning his age. He pauses, unsuccessfully attempting to maintain a scowl. “But I have the body of a 9-year-old.”

The staunchest of Clint Eastwood fans—and audiences for his newest movie, Honkytonk Man—won’t buy that. Nor would the women among them necessarily want to. Even Clint’s son, Kyle, drawing equal billing with Dad in his first major role, no longer has the body of a 9-year-old—he’s a gangly 14. But as some shirtless scenes in the flick will attest, Eastwood has no peer in Hollywood, or most other places in the country for that matter, in maintaining the tone and musculature of a man 20 years his junior. The deeply creased Eastwood face is another matter. “Kyle has dimples,” says Dad. “I’ve got pleats.”

Those pleats have worn well over the years, as has Eastwood’s seemingly bionic body. Fastidious attention to diet and fitness have seen to that. He pops vitamins (particularly C and B) the way some cowboys gobble jelly beans. “I take about a carload,” he jokes, and contends that his close-in vision has improved since he started megadosing. “Sondra [Locke] used to have to read the menus,” he says of his girlfriend of some three years and occasional co-star. In addition, he follows a low-fat, high-veggie diet and steers away from red meat. A piece of boysenberry cheesecake at the Hog’s Breath occasionally will tempt him, though.

Between films, as he is now, Eastwood works off calories with a daily mile beach run in the Monterey morning mist. Then there are afternoon sessions with the barbells or in his roman chair, a contraption that stresses his muscles. But the exercise he’s enjoying the most this winter is skiing in Sun Valley with Kyle, daughter Alison, 10, and Locke, 35. “She skis a little more conservatively than me,” Clint says of Sondra. But Kyle is fearless like Father. “He just gets out there and rolls,” says Clint.

Which is sort of the way Eastwood makes his movies. He calls Honkytonk Man a “little film,” and in the conventional Hollywood sense, it is. The shooting took just six weeks last summer, and he brought it in at $3 million, under his allocated budget. That last is a trademark of Eastwood, the producer-director. “It’s a little like a platoon,” he says of his veteran film crew. “I guide the platoon where it has to go.” At double time. Clint reckons that any other producer would have taken 10 weeks to get the raw film into the can.

Eastwood aficionados looking for Dirty Harry or Mitchell Gant, the supersonic plane thief of last summer’s $18 million Firefox, get a different Clint this time. In Honkytonk he is Red Stovall, a boozing country singer trying to achieve recording immortality before a fatal illness silences his guitar. “I like to take a chance with a vulnerable character,” says Clint. Otherwise, “You’ll never forge out.”

Kyle plays Eastwood’s nephew, who unsuccessfully tries to keep his elder on the straight and narrow. A proud Clint says of Kyle’s cinematic rite of passage, “I think he’s awfully good. He doesn’t overplay it, and he knows how to be economical.” Clint kept Kyle, now a ninth grader at a private school in Carmel, away from the professional academies that mold so many child actors. “You look at kids in TV commercials,” he says, “and see them being put through their paces by adults. It’s kind of embarrassing.” That’s not to say that Kyle free-lanced his way through the flick without guidance. Veteran actress Locke, who does not appear in the film, provided coaching, and there were some occasional firm pointers from the platoon leader. “He listened well and thought out the part,” says Clint. “When he didn’t, I was there to remind him.”

Putting Kyle in front of a camera was no surprise, says his director. “He’s a very natural kid, and he’s been totally immersed in film. He was always obsessed by it. Where other kids are watching Laverne & Shirley or some current sitcom, he’d much rather look at Of Mice and Men, the original [1939] version. That’s why I thought maybe he’d be able to handle that size of a part.”

For Kyle, the most enjoyable aspects of the role were those any 14-year-old would find appealing. “I liked stealing the chickens,” he says. “I also liked driving the car,” he adds with the enthusiasm of someone who is still 18 months away from getting a driving permit. Happily, some boyhood pleasures don’t change.

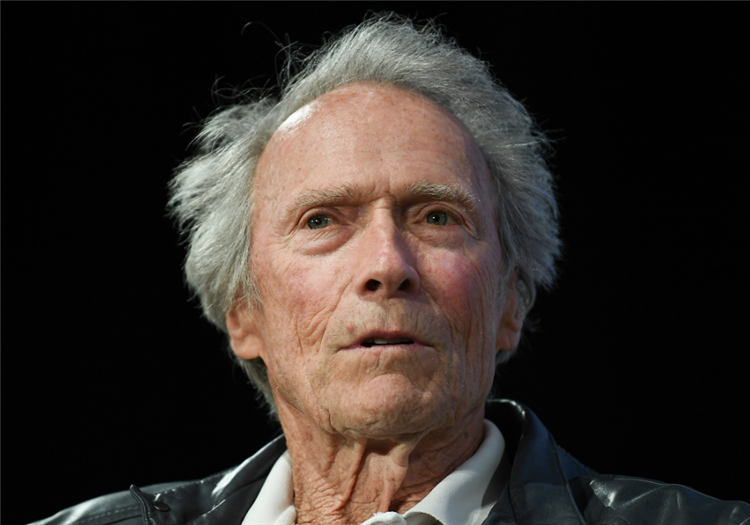

There is a sense of change about father Eastwood, though, a feeling that he is more willing to take liberties with his career. Clint says he no longer responds to the siren song of the box office, though his showbiz canniness has made him perhaps the most financially successful actor of his generation. “I don’t care about doing as much now,” he says. “In the old days I always felt I had to do more. Now it’s time to make some comments with my work that I’m interested in making. I’d hate to look back on my portfolio someday and think, ‘Well, I did 100 Magnum films and one car wreck film.’ I’d like to think that I had a broad career of various types of films and roles.”

There is also a more reflective Eastwood behind the camera. “I enjoy it more. I’m more organized and more patient.” And less prone to deliver an explosion per second, as he did with such films as The Gauntlet. Honkytonk Man moves with an almost stately—some would say painstakingly slow—pace. “I feel I haven’t yet hit my stride,” says Eastwood, in critiquing himself.

If Honkytonk Man is not a hit at the box office, it may produce one on the country-and-Western charts. The title cut (sung by Marty Robbins, who suffered a fatal heart attack just before the movie’s release) is a variation of the tried-and-true theme of love, lost and found. It follows such previous tunes from Eastwood sound tracks as Every Which Way But Loose, by Eddie Rabbitt, and Bar Room Buddies, sung as a duet by Eastwood and Merle Haggard in Bronco Billy. It also ought to make some money for the record company, Warner/ Viva Records, that Eastwood formed with producer Snuff Garrett two years ago.

Some 150 movie properties pass across Clint’s desk annually. “I know right away, and I rarely change my mind,” he says of the scripts he finally chooses. “I’d like to do a Western again if the right story came along.” Clint considers his last true Western, 1976’s The Outlaw Josey Wales (a box office as well as a critical success), one of his finest pieces of work. Any new script would have to be up to that standard.

Down the road, Eastwood may direct movies without acting in them. “There’s a great advantage to directing and not suiting up,” he says. “Acting can be boring.” He is even prepared for the actor’s ultimate fear—losing his appeal. “If it doesn’t maintain,” says the realist, “I can direct or still be involved in the film business.”

Eastwood prefers to spend time these days “with the squirts,” his children, who live with Maggie, from whom Clint legally separated in 1979. Their home is a fan-shaped redwood house Clint completed in 1976, which seems poised to take off from a magnificent rocky point near the famed Pebble Beach golf course. Hauntingly beautiful Monterey cypresses give way to ice plant, which yields only to the jagged rocks and the legions of seals frolicking in the surf.

Clint visits regularly, taking Kyle to the movies and Alison to riding lessons. Occasionally he’ll try his hand at Pac Man and Frogger, two of the four arcade games set up in his former weight room. He now lives quietly in a redwood house across the street from the beach and the Pacific, closer to Carmel. He also maintains a home in the L.A. suburb of Sherman Oaks, a 20-minute drive from his offices on the Warners Burbank lot. He is brusque when asked to plot out his personal future. “I’ve had one marriage that didn’t work, and I don’t know if I’d want to do that again,” he says. “Besides, I have a super gal in Sondra, who is very talented and career-oriented.”

Much of the Eastwood career—his mystique, if you will—has been built on a sense of elusiveness. Even after nearly 30 years in the public eye, only Clint knows what he’s thinking, and he’s keeping those thoughts private. But in a self-deprecating way, he provides a part of the answer: “Once people find out,” he says, “they’d probably be disappointed and wouldn’t care anymore. I’d blow the whole store.” That’s not likely. Not anytime soon.