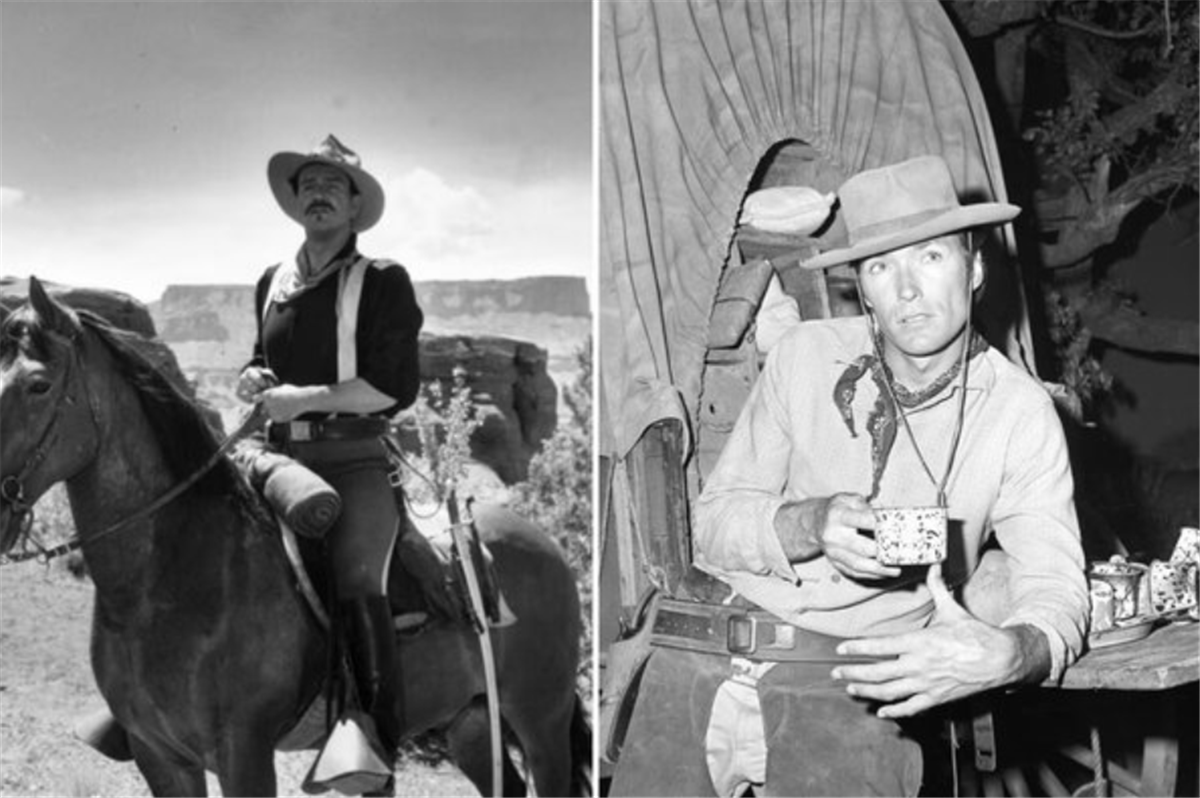

Turning 50 this year, High Plains Drifter was Eastwood’s first Western behind the camera. Though the actor’s rise to fame was rife with gunslingers of various moral outlooks, from early television roles such as Rawhide (1959-1965) to the brutal Italian classics of Sergio Leone such as A Fistful of Dollars (1964), it wasn’t until the 1970s when Eastwood started directing. And with the success of his accomplished 1971 debut thriller Play Misty for Me, it wasn’t long before Eastwood tried his hand at the Western. However, Eastwood’s film would typify the era’s dramatically pessimistic take on America’s Old West, to the point of being more a supernatural horror film than a classic gunslinger tale.

Scripted by Ernest Tidyman, famous for his Oscar-winning screenplay for William Friedkin’s The French Connection (1971), High Plains Drifter reflected a more modern approach to the genre in tone and content. It follows an unnamed stranger (Eastwood), who may, in fact, be a ghost, as he enters the town of Lago in search of vengeance for a US Marshal who was horse-whipped to death as the town looked on.

The atmosphere of the film is dark and tense, the violence is unforgiving and the sense of honour threadbare. Within the first 10 minutes, the stranger has tricked three men to their deaths and assaulted a woman. It perfectly summarises the tone of the new revisionist Westerns. “I’ve never pictured myself as the guy on the white horse or wearing the white hat on the mighty steed…” Eastwood admitted.

Eastwood’s film chimed with a new, grittier generation of Westerns, sitting comfortably alongside such classics as Robert Altman’s McCabe & Mrs Miller (1971), Arthur Penn’s Little Big Man (1970), and Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1968). These new Westerns often had a hopeless edge, dealing with down-and-out figures battling violently against poverty, the elements and each other. “High Plains Drifter was meant to be a fable,” Eastwood said, “it wasn’t meant to show the hours of pioneering drudgery. It wasn’t supposed to be anything about settling the West.”