For over half a century, Clint Eastwood has been a presence in the industry that’s equal parts iconic and indelible, with the actor and filmmaker experiencing more success than the majority of aspiring stars could ever possibly dream of.

With that in mind, it makes the studio system of his breakthrough period look resolutely idiotic when producers and executives all across Hollywood tried as hard as they possibly could to clip his wings. They wanted Eastwood the persona, neatly packaged and hand-delivered to their doors.

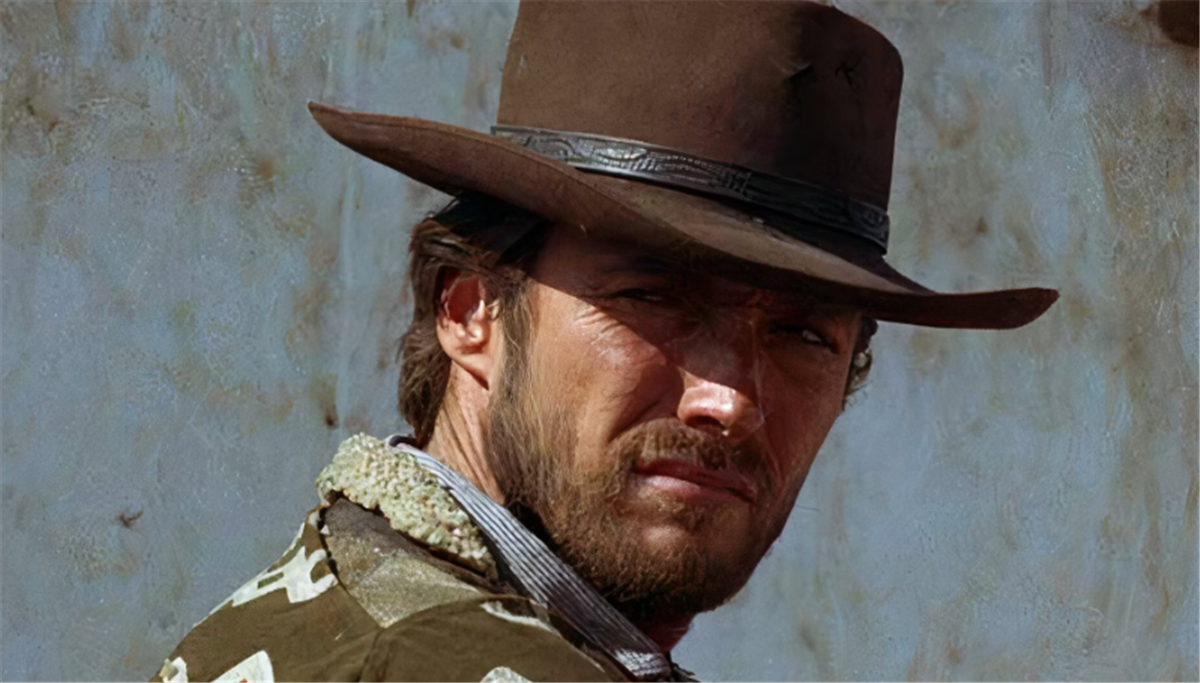

It was the smouldering charisma, rugged masculinity, thousand-yard stare, and natural gravitas that elevated him into that position in the first place, and the double-edged sword was that he’d have to fight twice as hard to be given the opportunity to do anything else.

Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More, and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly are all individual classics that combine to form an all-timer of a trilogy, and they couldn’t have been more beneficial to Eastwood’s career. He’d ventured over to Europe as a professional working actor and returned as a star, but that’s where the trouble began.

Because those films hadn’t been backed or produced by a major entity that was headquartered in the United States, it was as if he had to prove himself all over again. When he ended his overseas sabbatical and returned to home shores, there are no prizes for guessing which genre he immediately made his bed in.

As a handsome chap who’d thrived in genre fare, his following three pictures were western Hang ‘Em High, crime thriller Coogan’s Bluff, and action-packed war story Where Eagles Dare. Eastwood knew there were plenty more strings to his bow, but nobody lurking within the industry’s corridors of power was interested in plucking them.

“I had a lot of success with the westerns I made with Sergio Leone,” Eastwood admitted to Roger Ebert, but there were plenty of hurdles that still needed to be cleared. “But there was still this snobbishness from Hollywood studios. They weren’t ready to take me seriously.”

He was a bankable name, but only under specific parameters. When Hang ‘Em High “turned a profit in ten weeks flat,” Eastwood lamented how “they’d take me seriously as a cowboy but nothing else.” Coogan’s Bluff did much the same thing, albeit with a different caveat, because now the studios thought, “Maybe he can play a cop, too, but nothing else.”

Even after the trio mentioned above, Eastwood was stuck turning his wheels in styles he was already too well-versed in for his liking. OK, Paint Your Wagon saw him try and upend his mythos by adding a musical element to the western, but it didn’t pan out. Two Mules for Sister Sara was another oater, and Kelly’s Heroes plunged him back into the thick of wartime conflict.

Something had to change, and in the most fortuitous timing, it was lurking right around the corner. In what turned out to be the gift that kept on giving, Eastwood turned his hand to directing for the very first time in 1971’s Play Misty for Me, which was a million miles away from anything he’d done in years.

He wasn’t a cowboy, he wasn’t a cop, and he wasn’t pulling out a pistol to deal with his problems. Instead, he was Dave Garver, a radio host in a small coastal city trapped in an unhappy relationship who makes the mistake of cheating on his girlfriend, only to discover the woman is an obsessive fan who’d deceived him into bed and was more than ready to take their ‘bond’ to the next level.

In an instant, not only had Eastwood shown his chops as a talented director who could helm a hit that recouped its budget more than ten times over from cinemas, but he’d shoved it right in the face of his detractors to underline and place the exclamation point on the fact he was just as much of a draw and arguably an even better actor when he was cast as a regular joe.

Ironically, Play Misty for Me was released a mere two months before Dirty Harry premiered, and if he hadn’t made the former, then he may have never escaped from the typecasting and pigeonholing that the latter would have inevitably brought on.