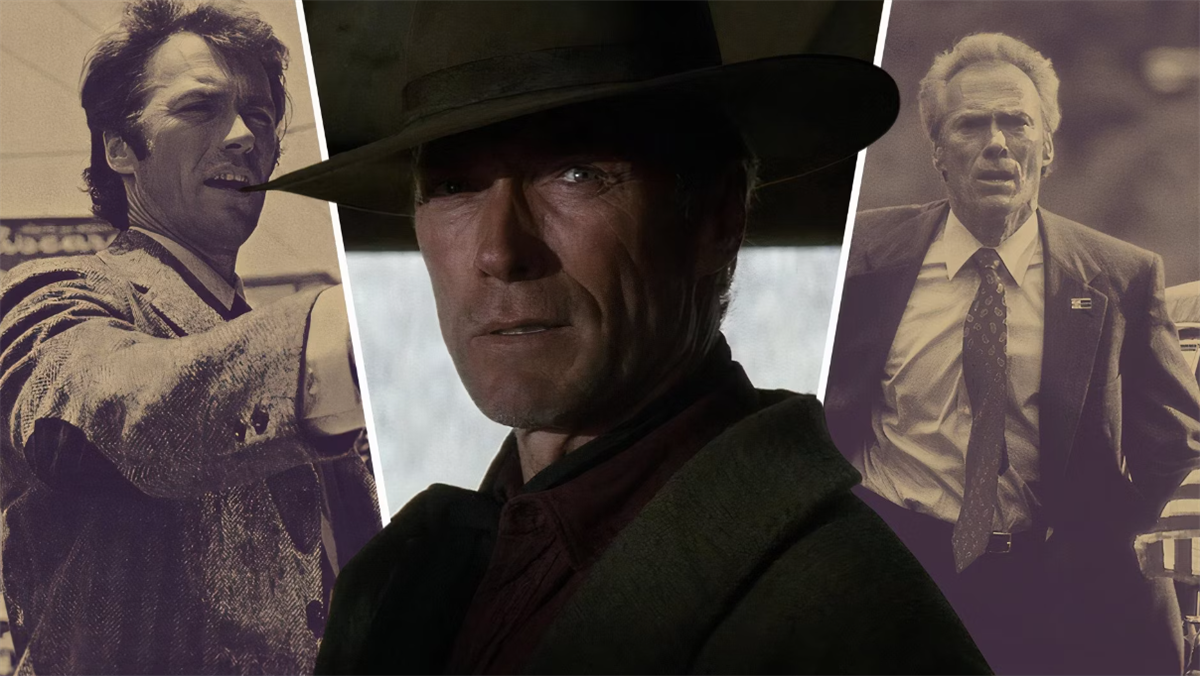

Over thirty years ago, Clint Eastwood starred in and directed his swan song, Unforgiven. The Best Picture winner was the Western to end all Westerns, a revisionist take on the genre that presented Eastwood at his most savage. The film’s widespread acclaim was positioned as a tribute to an exceptional career in Hollywood, but then Eastwood continued to keep making movies steadily for 30 years. Eastwood, now 94 years old, is supposedly working on his final film, Juror No. 2, and knowing how quickly Eastwood’s productions move, the film will likely be released in the blink of an eye. While he continued to act and direct following Unforgiven, he never touched the Western genre, instead focusing on neo-noirs and biopics of complex heroes of the 20th and 21st centuries. However, enough time had passed for him to get back in the saddle (or at least attempt to), and finally realize a long-gestating project, Cry Macho, a curious neo-Western inseparable from the actor’s iconography.

The Decades-Long Development Period of ‘Cry Macho’

Clint Eastwood’s career is so prolific that he has lived long enough to experience the era of day-and-date release, when, to balance COVID-19 health concerns and the livelihood of the theatrical industry, Warner Bros. simultaneously released films in theaters and on Max (then HBO Max) in 2021. Released in September, Cry Macho follows an old Texas rodeo star, Mike Milo (Eastwood), who accepts a job from his former boss, Howard Polk (Dwight Yoakam), to retrieve his son, Rafo (Eduardo Minett), from rural Mexico away from his alcoholic mother. In a character arc similar to Eastwood’s Gran Torino, Mike learns to evolve and redeem himself by guiding the teenager through life. Eastwood loves road trip dramas as much as Westerns or police thrillers, as Cry Macho cribs from both A Perfect World, about an ex-con and a young boy evading law enforcement on the open road, and The Mule, about an elderly horticulturist-turned-drug courier who learns about himself during his trips.

Cry Macho, met with mixed reviews upon release, was a project stuck in development hell for 30 years. The film was conceived in the 1970s by N. Richard Nash, who turned the script into a novel to increase its chances of publication. There was little progress in adapting the book into a feature film until Albert S. Ruddy, the late producer of The Godfather and subject of the Paramount+ series, The Offer, bought the rights to the book. Ruddy spent decades getting Cry Macho off the ground. In 1988, before he was an Academy Award winner, Eastwood received an offer from The Godfather producer to star as the aging rodeo cowboy in Cry Macho, but he refused. When speaking to the Los Angeles Times, he recalled telling Ruddy he was “too young” for the role. However, he proposed directing the film with an age-appropriate star, with his endorsement being Robert Mitchum, then in his early 70s. While Eastwood was only in his 50s, he convincingly played grizzled and seasoned characters at a young age. Few could’ve imagined a 90-year-old playing any protagonist on screen, let alone the lead in this modern Western.

Arnold Schwarzenegger Almost Starred in ‘Cry Macho’

The plan for Eastwood to direct Mitchum in Cry Macho never panned out, and the project stalled for another decade. Eastwood opted to play Harry Callahan for the fifth and final time in 1988 in the film, The Dead Pool. Arnold Schwarzenegger showed interest in the film in the early 2000s, but he was sidetracked by his duties as Governor of California. Following his tenure in public office, he returned to the project, and the film was positioned as his long-awaited Hollywood comeback after two gubernatorial terms, with Schwarzenegger discussing its development in the press. With The Lincoln Lawyer director Brad Furman tapped to direct, Ruddy teased Schwarzenegger’s Cry Macho as a never-before-seen look for the actor, stripping away his brutish persona and instead showing his vulnerable side. For Eastwood, the film signals a coda, but for Schwarzenegger, Cry Macho served as an evolution to the next phase of his career. However, the film was suddenly delayed and eventually canceled altogether in the wake of the unfolding scandal surrounding the child he fathered while married to Maria Shriver.

Eastwood belongs to a rare club of actors and filmmakers who are granted a lifetime blank check from a respective studio, Warner Bros in his case. With little studio interference, Eastwood, thanks to his habit of staying under budget and producing profitable films, has earned creative autonomy. “I always thought I’d go back and look at that,” Eastwood told Kenneth Turan of the LA Times, referring to Cry Macho. “It was something I had to grow into.”Instincts have driven Eastwood throughout his career, never thinking of acting as an “intellectual sport.” If his instincts tell him to star and direct a film in his 90s, he won’t hesitate to follow through. Contributing to the obstacles of Eastwood’s age and cast primarily consisting of inexperienced actors, the film was shot in 2020 amid the throes of the pandemic.

How ‘Cry Macho’ Connects to Clint Eastwood’s Screen Persona

While Eastwood has frequently returned to the well of elderly men bewildered by modern times, notably in Gran Torino and The Mule, Cry Macho is the actor-director’s most soulful and poignant expression. Even if it feels like Eastwood has been in his swan song for 30 years, his most recent film strongly suggests a career capstone to his screen persona. For someone who could feasibly ponder death and the sanctity of life every day, Eastwood embraces his elder status, telling the LA Times that his age offers “more interesting guys you can play.”Cry Macho, in the most endearing way, feels like it was directed by a nonagenarian. It’s hard to deny that the film is dramatically inert and awkwardly paced. For any other film, these would be the clearest symptoms of a poorly made film. Yet, for whatever inexplicable reason, Cry Macho remains fascinating due to its deep connection to its star and director. The title is a riff on the natural tendency for cowboy figures to flex their masculinity. In the film, Eastwood, who’s always been more sentimental compared to his image as a symbol of unbridled virility, plays a character who learns that his old posturing ways gave him nothing to show for in his personal life.

With its nonchalant tone and disregard for dramatic stakes, Cry Macho defines late-period Clint Eastwood. It’s only fitting that the project’s development began and ended with Eastwood, as the story of a rodeo cowboy who prefers to spend time with a rooster rather than partaking in perilous adventures complements this phase of Eastwood. If this ultimately became an Arnold Schwarzenegger vehicle, it likely would have been approved by more critics and made a bigger dent at the box office, but it surely would lack the uniqueness of Eastwood’s film. Despite his status as an icon of the genre, the film is not bound to the norms of Westerns. Some may reasonably call the film lazy and rushed, but Eastwood understands the power of his screen presence. The average viewer will watch him struggle to mount a horse or belly-up to a local bar without any conflict in the story. Cry Macho may not have much to say about the Western genre, but it does meditate on the life of a Hollywood legend in his seventh decade of filmmaking.