Clint Eastwood has been such a familiar force in American cinema for so long that it’s easy to think you’ve got him figured out. Yet here he is again, at 94, with a low-key, genuine shocker, “Juror #2,” the 42nd movie that he’s directed and a lean-to-the-bone, tough-minded ethical showdown that says something about the law, personal morality, the state of the country and, I’m guessing, how he feels about the whole shebang. He seems riled up, to judge from the anger that simmers through the movie, which centers on a struggle to find justice within — though perhaps despite — an imperfect system and in the face of towering self-interest.

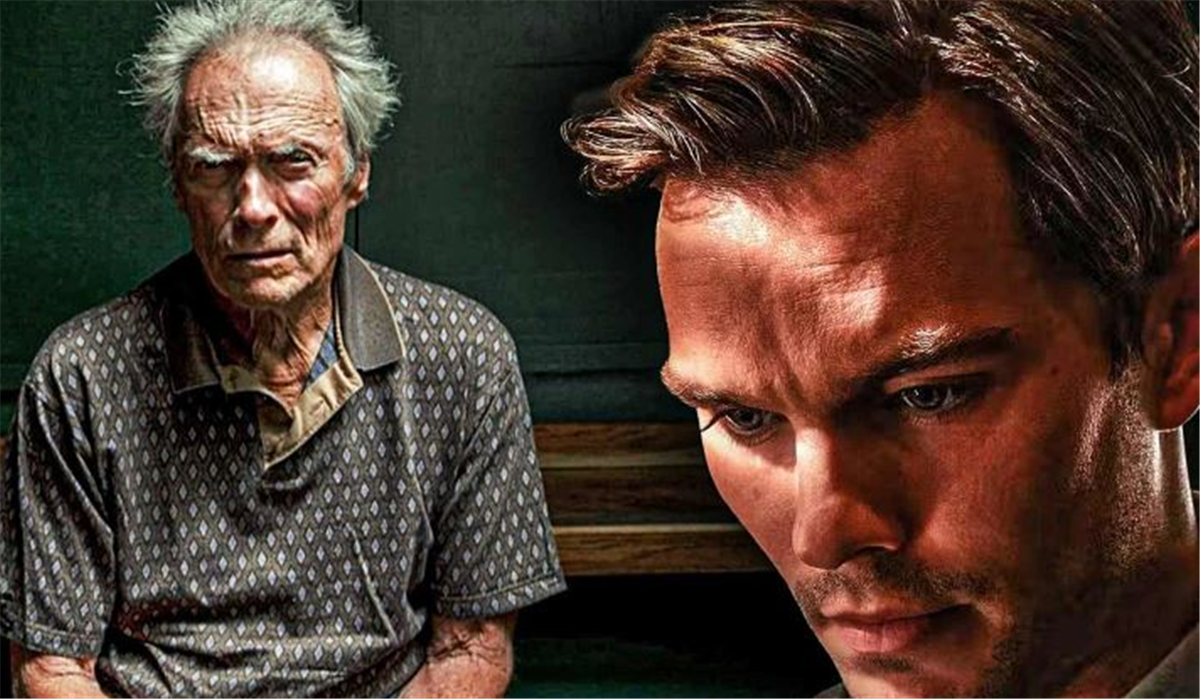

Justin (a very fine Nicholas Hoult) has just finished fixing up a baby nursery at home when he walks into a Savannah, Ga., courtroom to report for jury duty. He and his wife, Allison (Zoey Deutch), are expecting, and tying themselves into knots of worry because several years earlier, their last pregnancy ended tragically. For them, his civic duties couldn’t have come at a worse time. Even so, Justin shows up, eager and attentive, and before long is seated on a jury in a criminal case that takes an abrupt, unexpected turn: The defendant has been charged with murder, and Justin quickly realizes that he himself might be the real killer.

Did he or didn’t he is one question, and the start of a mystery, both procedural and existential, that soon finds Justin playing at once a freaked-out juror, potential culprit and dogged detective. The defendant on trial, James (Gabriel Basso), has been accused of murdering his girlfriend, Kendell (Francesa Eastwood, the director’s daughter). They’d been drinking at a local dive when they began arguing. They went outside, where it was dark and pouring rain, and continued to fight in front of a smattering of customers who had followed them. She walked off alone, he trailed after her in his truck, and before long she was dead.

It’s a deliciously twisted setup, like something out of an old film noir in which the hero becomes the main suspect and, by desperate default, also slips into the role of a detective working the case. In this movie, voir dire has scarcely ended — Eastwood, who famously likes to work fast, races through the typical preliminaries — when Justin is sweating in the jury box and listening to the prosecutor, Faith (Toni Collette), and the defense lawyer, Eric (Chris Messina), make their cases. Before long, the lawyers have made their closing arguments, and Justin is sequestered in a room with 11 people who are also on the case.

Eastwood takes a bit of time to find his groove. The opener is, by turns, pokey and rushed, and you can almost feel his impatience as he lines up the story’s pieces. He doesn’t seem to have spent much time thinking about the movie’s visuals; they look fine, I wish they looked better. He seems especially uninterested in Justin’s home life, and given how dreary and claustrophobic it looks, you can hardly blame him. Once the trial begins and the lawyers start prodding and probing, Eastwood settles in nicely. Justin realizes that he was at the bar the same night as the defendant and victim, triggering a series of jagged flashbacks that, as the trial continues, grow longer, more detailed and, in time, help fill in the larger picture.

Written by Jonathan A. Abrams, “Juror #2” is a whodunit in which justice turns out to be as much on trial as the defendant. Both sides seem to have a weak case. The defendant is shady, the autopsy inconclusive, the only witness questionable, and there’s an enigma among the jurors, most of whom just want to go home. And while Eric nevertheless delivers a righteously indignant defense, Faith seems overly eager to wrap things up, partly because she’s running for district attorney and already fake-smiling like a glad-handing politician. Their arguments are shrewdly handled, pared down and delivered in a dynamic volley of edits that turn their speeches into a he-said, she-said duel, with a stricken Justin caught in the middle.

Flashbacks, when overused, can leach energy from a story, but the ones in “Juror #2” help build suspense. Each glimpse from the past offers another murky image from Justin’s slow-dawning memory, but they also help sketch in his character and history. Justin is a classic Everyman (there’s a touch of Jimmy Stewart in Hoult at his most skittish), a sympathetic guy with family bona fides and a tragic past that makes him more appealing. He used to drink (Kiefer Sutherland shows up as his sponsor), but he’s straightened out, maybe, possibly. Justin isn’t altogether clear about that dark, stormy night, which means that you aren’t, either, and the question of his guilt or innocence only grows more complicated in the jury room.

As usual, Eastwood has populated the cast with appealing professionals, and it’s a kick to see Hoult and Collette reunited: They played mother and son in the 2002 film “About a Boy.” The jury is packed with a particularly good mix of faces and types, with J.K. Simmons as a worryingly inquisitive retired cop and a memorably grave Cedric Yarbrough as one of the jurors who announces “guilty” almost immediately on entering the jury room. Eastwood doesn’t take obvious sides, which effectively puts you on the same deliberative level as the jurors. Yet as the arguments for and against a conviction ebb and flow, and Justin struggles with the case, as well as his memory and his fears, questions of culpability become murky.

Several times in “Juror #2,” Eastwood cuts to a statue of Lady Justice that stands right in front of the courthouse, her scales gently swaying as if from an otherwise undetected wind. As visual motifs go, it could not be much blunter, even if the first time it appears onscreen, it seems more like ornamentation than a declaration of principles. Over time, though, as the story gathers momentum and its mystery deepens, the symbolism of those rocking scales becomes increasingly stark. Eastwood has explored systemic injustice before, including in “Changeling” and “Richard Jewell.” This is a stronger movie than those two by far, and if this one proves, as rumors have it, that it’s his last as a director, he is going out with a bang.