Thanks to his rumbling baritone and immaculate diction, hearing Orson Welles read the phonebook would have been an enjoyably engaging experience, but the famously acerbic auteur tended to be at his best when he was in full-blown evisceration mode.

The mastermind behind Citizen Kane hated an awful lot of people and an awful lot of things about Hollywood, and he wasn’t shy in letting it be known. Welles’ loquacious takedowns of anything that dissatisfied him are best read imagining his voice, adding a little extra oomph to his double-barrelled assault on the industry.

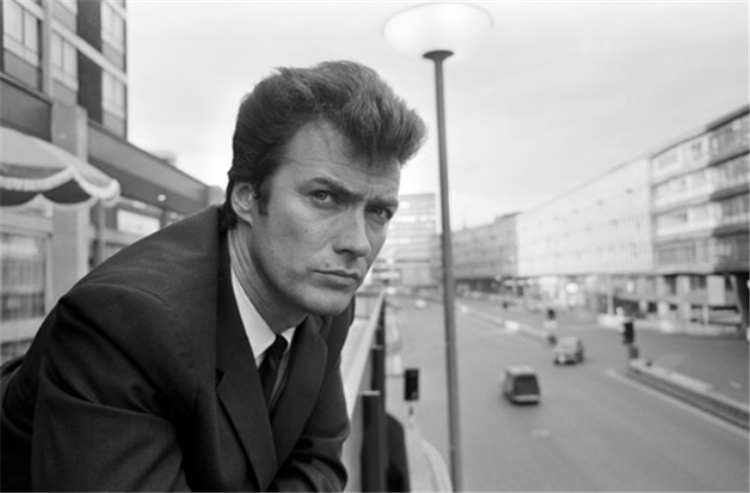

Not that he was defined by his disdain and bitterness, though, with the mercurial talent equally fond of praising those he believed deserved praise. It might sound bizarre in a modern context to describe Clint Eastwood as being underrated in any respect, but even superstars have to prove themselves when they take up a new vocation.

After conquering the on-screen Western, Eastwood segued behind the camera to make his feature-length directorial debut on 1971’s psychological thriller Play Misty for Me, before returning to the genre that made his name in sophomore effort High Plains Drifter. He followed that up with romantic drama Breezy and actioner The Eiger Sanction, before donning his wide-brimmed hat once more with The Outlaw Josey Wales.

It may have been his fifth movie as a director, but Welles maintained during an appearance on The Merv Griffin Show that the actor-turned-filmmaker hadn’t yet been given his due. “Clint Eastwood is the most underrated director in the world today,” he said. “I’m not talking about him as a star.”

“They don’t take him seriously, the way they don’t take beautiful girls seriously,” Welles continued by furthering his analogy of Eastwood being too handsome for auteurship. “They can’t believe they’re intelligent if they’re beautiful, they can’t believe they can act if they’re beautiful, they must be forgiven.”

After watching The Outlaw Josey Wales, Welles reflected on the leading man’s status as “a pure type of mythic hero in the [John] Wayne tradition,” which by extension meant “nobody’s going to take him seriously as a director.”

Fortunately, he was happy to become a vocal backer because, in Welles’ mind, “somebody ought to say it.”

These days, it’s not exactly a controversial opinion to call Eastwood a top-tier director because he’s got two Academy Awards apiece for ‘Best Picture’ and ‘Best Director’ to show for it, never mind a prolific output that’s only increased in volume the longer he’s been in the game.

Needless to say, things weren’t quite the same in the mid-1970s, but Welles was ready to fight his corner and salute the icon’s craftsmanship during a period where he was still trying to convince the world there was more to his directorial sojourn than massaging the ego.