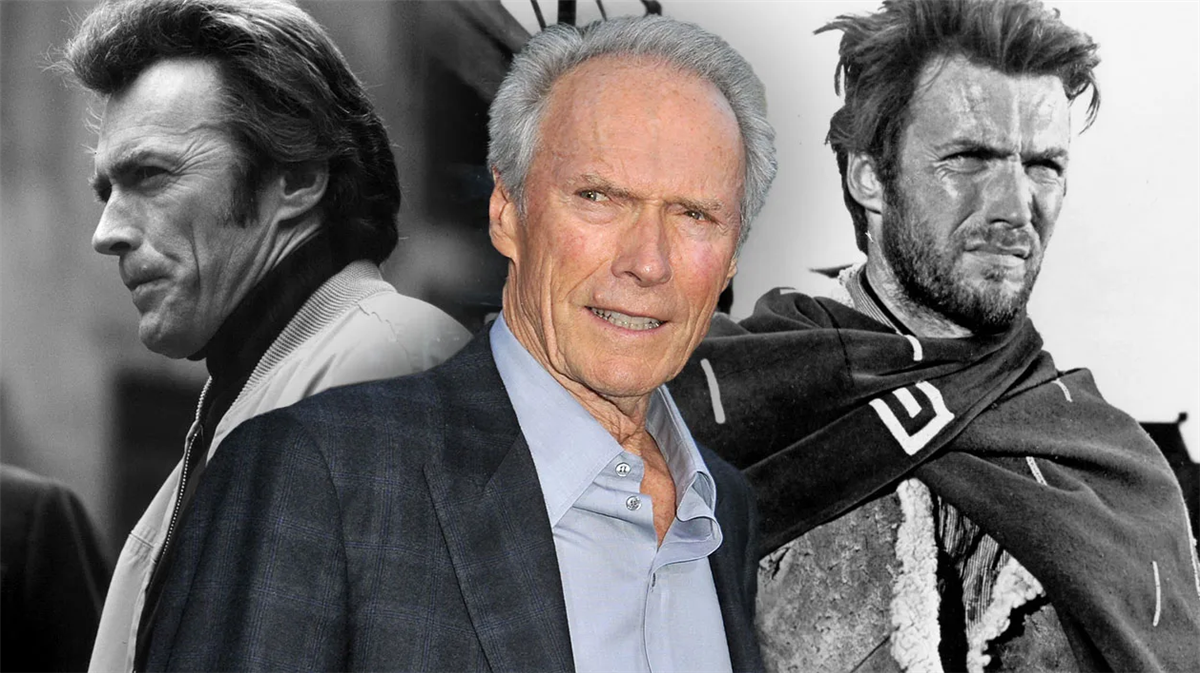

In the history of Hollywood, no figure was quite as reflective of their image, star persona, and stature in the industry as Clint Eastwood. While he is a tried and true action movie star, frequently playing gun-toting outlaws who defy the orders of society, Eastwood has aspired to deconstruct the archetypes of cops and cowboys on screen throughout his illustrious six-decade career as an actor and director. He is symbolic of seemingly contrasting tastes. He can seamlessly give audiences a satisfying thriller about revenge featuring copious amounts of gun fights, yet his most accomplished films confront the harsh underbelly of violence. With his 1976 Western The Outlaw Josey Wales, Eastwood examines violence in the context of America’s past and present relationship to warfare.

What Is Clint Eastwood’s ‘The Outlaw Josey Wales’ About?

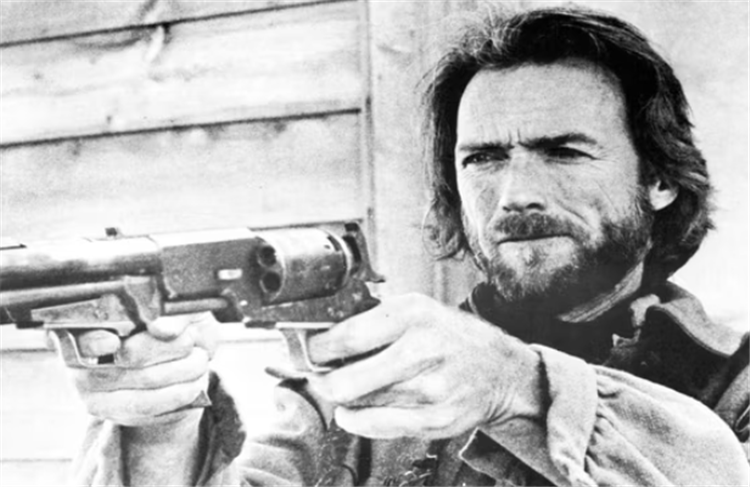

The Outlaw Josey Wales follows the titular Missouri farmer (Eastwood) who joins a Confederate guerrilla military unit after the slaying of his family by Union soldiers. Eventually, as he emerges a feared gunfighter, Wales becomes the target of a manhunt by the same Union soldiers and a gang of bounty hunters. On the surface, Josey Wales appeals to the cheap sensibilities of exploitation pictures.

The film, from its synopsis to its perspective, centered on the Confederacy during the Civil War, seems like trashy and troubling material that is beneath Eastwood. In the end, the film’s confrontation with transgressive topics and circumstances leaves an immeasurable impact on the final product, as Eastwood’s sobering commentary on the brutality and bleak inevitability of war is some of the star’s most resonant storytelling.

Clint Eastwood Interprets ‘The Outlaw Josey Wales’ as an Anti-War Film

In a 2011 interview with The Wall Street Journal, in the lead-up to his upcoming biopic, J. Edgar, Eastwood opined on the ethics of law enforcement and reflected on his military experience in the Korean War. His sympathy towards law officials (from the real-life J. Edgar Hoover to Gene Hackman’s Oscar-winning turn as “Little” Bill Daggett in Unforgiven) who seek proper justice but are derailed by an excess of chivalry is an insightful portrayal of his vast filmography. Ultimately, the subtext of The Outlaw Josey Wales crystallizes Eastwood’s belief that the nobility of justice is destined to be undermined by a warmonger complex that permeates American politics.

More so than any of his explicit war films, including Letters from Iwo Jima or American Sniper, Eastwood labeled Josey Wales as an “anti-war” film. “I saw the parallels to the modern day at that time. Everybody gets tired of it, but it never ends,” he said, comparing the film’s narrative to the contemporaneous turmoil ensuing during the Vietnam War. Eastwood identifies a solemn reality surrounding war’s existence, stating that “war is a horrible thing, but it’s also a unifier of countries.” According to the actor-director, civilization perversely coexists and sparks genuine camaraderie among people during these years of bloody havoc. Humans are also at their most creative, as evident by the mass development of advanced weapons and machinery. “That’s kind of a sad statement on mankind, if that’s what it takes,” he remarks.

Clint Eastwood’s Josey Wales Wants Revenge

Indeed, camaraderie is an essential fabric of the story of The Outlaw Josey Wales. Following the harrowing murder of his wife and young son, led by Captain Terrill (Bill McKinney), he sharpened his skills as a gunfighter. Along his journey of vengeance, he forms a brief alliance with a Confederate guerrilla army before their subsequent surrender and killing at the hands of the Union soldiers. Soon after, Wales forms a pact with an assortment of misfits, including a Cherokee man, Lone Watie (Chief Dan George), a Navajo woman, Little Moonlight (Geraldine Keams), an elderly woman from Kansas, Sarah Turner (Paula Trueman), and her granddaughter, Laura Lee (Sondra Locke, who developed a personal relationship with Eastwood). In the film’s early moments, immediately after his family is massacred and his home is destroyed, the Confederate army emerges in the background. A distraught Josey, at his lowest moment, is given a chance for payback. This feeling of worth and validation is the root of the film and its harsh commentary on how warfare captures the emotional vulnerability of Americans.

The core structure of The Outlaw Josey Wales calls for a lone outlaw to exact brutal revenge on anyone who walks in his path. However, the tribal complex involved in the conflict between the Union and Confederate armies and Native Americans versus their local oppressors draws Wales into the orbit of traditional warfare. What started as a primal streak of vengeance evolved into a series of battles and disputes between other gangs and Native tribes, including the Comancheros and the Comanche tribe, respectively. Wales’ companions that he encounters along the way are also subjected to his journey of retribution. The character’s personal stakes blend in with the greater machinations of tribal warfare. Despite being set in a familiar Western setting filled with vistas and horseback riding shootouts, Josey Wales takes on the likeness of a man-on-a-mission war epic, such as the Eastwood-starring World War II film, Where Eagles Dare.

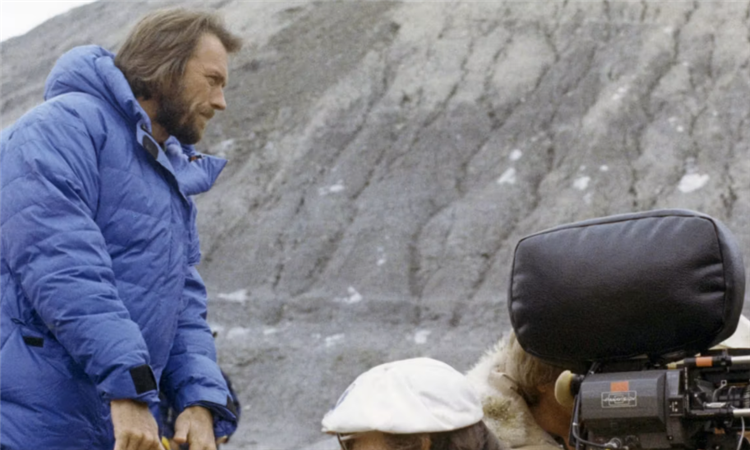

Clint Eastwood’s ‘The Outlaw Josey Wales’ Is a Smartly Directed Western

Beyond the thematic crux of the story, Eastwood’s film is visually rendered like a combat picture. The cinematography of Bruce Surtees, a frequent collaborator of Eastwood, and his filmmaking mentor, Don Siegel, shoots the Western vistas and rural villages with a distinct grain. The weathered landscapes of Missouri, Kansas, and the U.S.-Mexico border are antithetical to the glossy, painterly images created by John Ford, the definitive visionary of Western iconography. The gritty visual aesthetic is complemented by the direction of action sequences, which are stripped away of the elegance of a pistol duel in classic Westerns. The fast cuts and unstable camera movements create the sensation of being in the middle of an intense military clash.

In the film, Union and Confederate armies are equipped with advanced weaponry, including a Gatling gun that Wales used to attack the opposing soldiers during the Confederacy’s surrender. Wales operates as a military tactician, methodically executing schemes such as shooting off a rope that is attached to a Union vessel, subsequently trapping them in the middle of a body of water, or creating a diversion by placing a corpse on top of a riding horse to draw out soldiers at a camp. Eastwood’s proclamation to the WSJ that war brings out the most ingenious qualities in humans was clearly practiced when directing Josey Wales.

Violence Is an Inevitability in ‘The Outlaw Josey Wales’

Eastwood’s films, from his brash, free-spirited vigilante characters (notably “Dirty” Harry Callahan) and his experience in the Western genre, are loosely connected to his libertarian politics. Even in the scenarios where he plays a law enforcement official, his characters are proudly anti-government. In The Outlaw Josey Wales, Eastwood struggles to uphold his identity as a lone wolf. When Wales embarks on his quest following the encounter with Lone Watie and Little Moonlight, he says to them, “Might as well ride along with us. Hell, everybody else is.”

The powers of the military-industrial complex limit his independence. This is an especially noteworthy thematic trait because of the film’s genre. Westerns are about open fields and conquering uninhabited and non-industrialized lands. The climactic battle between Wales and Terrill takes place outside a fortified ranch where the outlaw’s companions take shelter. A settlement that should present itself with tranquility is shattered by the carnage of warfare between Wales’ pact and Terrill’s army.

Eastwood’s quote in the Wall Street Journal story informs an inevitability surrounding America’s reckless involvement in war activity. Regardless of one’s desire for bloody vengeance, warfare is destined to hit the American homefront. “Sometimes trouble just follows a man,” Wales reckons before riding off to battle. Viewers may interpret this line as a moment of self-reflection or obliviousness on the character’s part. It carries the weight of Western myths while signaling the pathos of violence that Eastwood strives to connect with in his direction. The oppressive nature of Wales’ violent plight is primarily self-inflicted, as he is not a pure hero in this story, but it complements his relationship with Native American people. Far more effectively than even the greatest Westerns in history, Josey Wales’ depictions of Native Americans are quite sympathetic, as the titular character takes solace in their oppression by the American government.

‘The Outlaw Josey Wales’ Is Reminiscent of John Ford’s ‘The Searchers’

The beauty of the Western genre is that each film, to varying degrees, is reflective of other films in the canon. As for The Outlaw Josey Wales, the mediation on the waning sense of nobility when carrying out justice belongs to the spirit of John Ford’s greatest achievements. The DNA of Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy starring Eastwood is also evident in the 1976 film. Furthermore, Eastwood’s widely recognized revisionist Western masterpiece Unforgiven, can be interpreted as a spiritual successor to Josey Wales.

Like every Western that arrived in its wake, the film is indebted to Ford’s The Searchers, just on the merit of Josey Wales’ closing line alone. Before riding off into the sunset, Wales, after overhearing Fletcher (John Vernon) enlightening a pair of Texas Rangers about the story of the outlaw’s (who is believed to be dead) trail of vengeance, remarks “I guess we all died a little in that damned war.” As a film released just one year following the end of the Vietnam War, this line unabashedly conveys the gloomy American sentiment of the period.

In The Searchers, Ethan Edwards (John Wayne) returns from the Civil War as a broken soul, and resorts to savage retribution against a Native American tribe. In his worldview, the war never ended. For Josey Wales, a once average American, combat is a rudimentary facet of life. Even if his past traumas are healed, he will always encounter violence along the way.