When an obscure Italian director, Sergio Leone, teamed up with an obscure T.V. actor, Clint Eastwood, in 1964 to make a ‘Western,’ titled “A Fistful of Dollars” in Europe, it made cinema history. Though a few Westerns have been made in Europe before Leone’s effort, they never had this distinct signature that Leone imparted to his Western. This very stylish, ultra-violent, cynical take on American Westerns emerged as a subgenre on its own, called “Spaghetti-Westerns.” That’s not all, the success of the first “Dollars” film revitalized the Italian film industry, with copycat versions of Leone’s film flooding the market, and becoming successful as well. Leone’s next film with Clint, 1965’s “For a few Dollars More,” was an even bigger success than the previous one, proving the popularity of Spaghetti Westerns with the masses. By the time Leone embarked on his third film with Clint, “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly,” there were about 500 Spaghetti Westerns in production in Italy. The copycatting had reached such absurd levels that there were even stars named Clint Westwood, and directors named John Fordson in circulation. The films were becoming more and more violent, and more and more ugly-looking, devoid of the classy visual sense and production values that Leone imparted his films. Leone become sick of seeing what he had brought about. He realized that if he had to stand apart from the rest, he will have to do something different and big, and hence decided to make the third film a true epic on the lines of a ‘David Lean’ film. Lean’s Oscar winning epic, “Lawrence of Arabia” that was released a couple of years ago was still running all over Europe, and it inspired Leone to set his new film in the background of a true and grand historical event. Since this is a ‘Western’, he chose the American civil war as the background- especially the period from 1861 to 1862, when Confederate General Sibley was making his big push from Texas into New Mexico, and was being beaten back by Union General Canby. Though no date was specified for the two previous “Dollars” films, it has to be assumed that both takes place after the civil war, so this film becomes a prequel of sorts to those two films.

The plot of the film, which Leone developed with a new set of writers, is pretty thin, but then when has the basic plot being of much importance in any Leone film. The emphasis here, as always, is in its making; in the visual and aural style of the picture, in its dark, ironic humor, in the moments of extended silences, the quirky characterizations, long build-ups to big scenes of violence, the ‘meta’ reflections etc. etc. But since this is set in the backdrop of the civil war, we get big set-pieces, like spectacular battle sequences and blowing up of bridges. The plot of the film goes something like this: Stevens, Baker and Jackson are three confederate soldiers who are put in charge of transporting a box of gold coins during the early days of Civil war. They run into a Yankee ambush, in which all three are wounded and the cash box disappears. The military high commands institutes an investigation into the incident, and all three are cleared, but the cash-box is never recovered. Stevens, who was crippled in the ambush, retires to his farm with his family, while Jackson changes his name to Bill Carson and reenlists in the Confederate cavalry. Baker, who was also injured in the incident, suspects that Jackson has stolen the gold and hidden it somewhere. He hires a ruthless killer & tracker, Angel Eyes (Lee Van Cleef), to kill Stevens and track down Jackson- all for a price of $500. Realizing that Jackson has changed his name, and Stevens must know his new name, Angel Eyes interrogates Stevens at his farm house. During the conversation, Stevens let slip that Baker is after the box of gold (something Angel Eyes was not aware of), and tells him that Jackson is going by the name of Carson. Realizing that Baker wants him dead, Stevens offers Angel Eyes $1000 to spare him and kill Baker instead But the thorough professional that he is, Angel Eyes kills Stevens (as well as his elder son), then comes back to Baker’s place, give him the information he wanted, and then kill him too- fulfilling his contract to Stevens. Now Angel Eyes is free to pursue the gold himself.

It’s while taking a sniff out of Jackson\Carson’s snuff box (which will prove to be important to the plot later) that, suddenly, Jackson comes to life. He asks for water , and promises Tuco to give him information about the stolen gold, which he has buried in “Sad Hill” cemetery. But before Jackson could tell him the name of the grave, he passes out. Tuco runs to get water, but by the time he returns Jackson is dead. And to Tuco’s anger and surprise, he finds Blondie- who had somehow crawled towards the carriage- lying slumped besides Jackson’s corpse. When Tuco once again attempts to kill Blondie, the latter informs him that before dying Jackson told him the name of the grave in which the gold is buried, and if Tuco wants to have it, he will have to keep Blondie alive. Now once again, Tuco and Blondie become partners- each sharing one half of the secret that will take them to the Confederate gold. Tuco takes Blondie to a monastery, where Blondie recovers; then they go forth to find the gold. But since both of them are impersonating Confederate soldiers, they are captured by Union soldiers and brought to a POW camp. To their surprise, the find that Angel Eyes- who they know from before – is the Union Sergeant in charge of the camp. Angel Eyes had infiltrated the camp looking for Jackson\Carson. Finding Carson’s snuff box in Tuco’s possession, Angel Eyes suspects that Jackson has conveyed the secret of the missing gold to Tuco. He has Tuco brought to his tent and tortured- during the course of which Tuco reveals the name of the cemetery in which the gold is buried, as well as the fact that Blondie knows the name of the grave. Angel Eyes, knowing fully well that Blondie will never divulge his secret during torture, decides to partner him up. Tuco is sent away to be killed, while Angel Eyes, with five of his men, and Blondie sets out to find the gold.

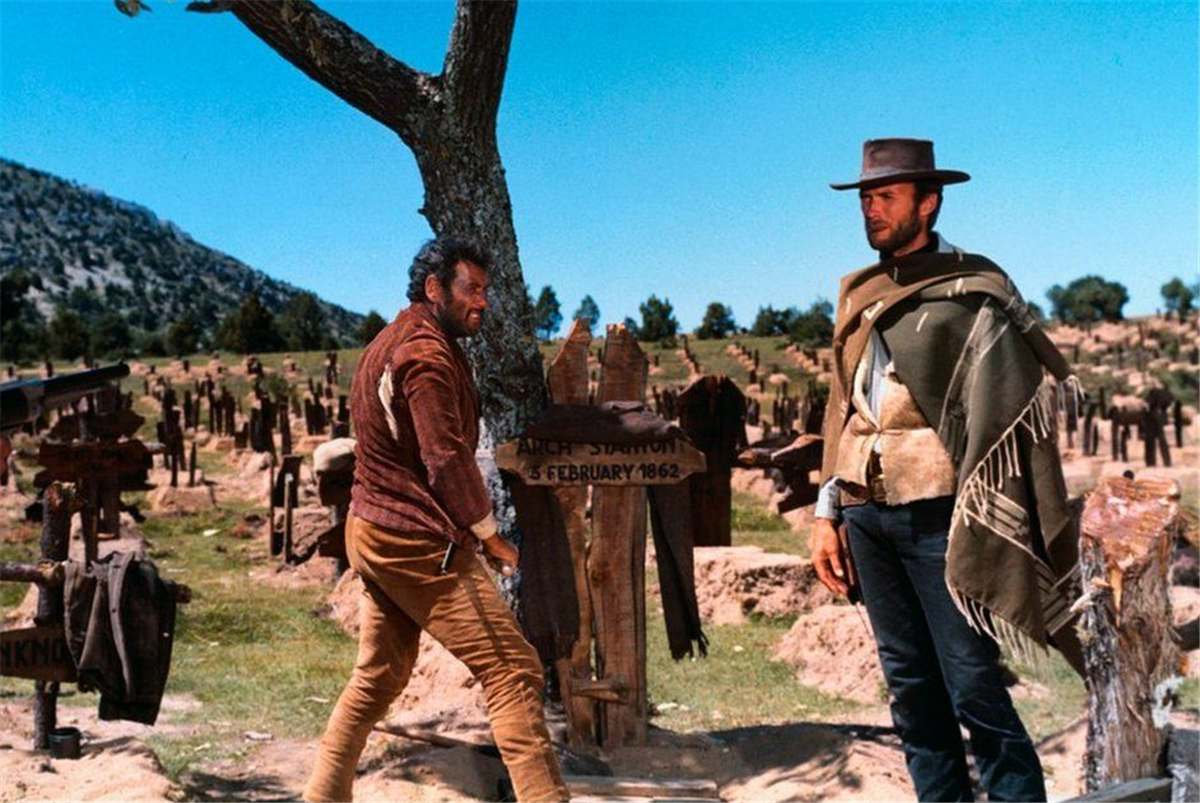

But Tuco manages to escape, and all the principles converge in the town of Peralta, which is reeling under cannon fire. Blondie finds out that Tuco is in town; he manages to slip away from Angel Eyes and his men, and join up with Tuco. Now Tuco and Blondie are together again, and they they go after Angel Eyes- who escapes after seeing Blondie and Tuco finishing off his men. After that the duo travel towards Sad hill cemetery. they briefly gets caught up in the war, but manages to extricate themselves from the situation by blowing up a strategic bridge, and thus clearing their way to their destination. Upon reaching the cemetery, Tuco races to find the grave of “Arch Stanton”- Blondie and Tuco had told each other their half of the secret while blowing up the bridge. Once Tuco finds the grave, he starts greedily digging it. Soon Blondie arrives, and asks him at gunpoint to continue digging . Then, to their surprise, Angel Eyes also arrives, and holds Blondie at gunpoint. Blondie states that he lied about the name on Stanton’s grave and writes the real name of the grave on a rock before challenging Tuco and Angel Eyes to a three-way duel. The trio stares each other down. Everyone eventually draws with Blondie killing Angel Eyes, while Tuco discovers that his own gun was unloaded by Blondie the night before. Blondie reveals that the gold is actually in the grave beside Arch Stanton’s, marked “Unknown”. Tuco is initially elated to find bags of gold, but Blondie holds him at gunpoint and orders him into a hangman’s noose beneath a tree. Blondie binds Tuco’s hands and forces him to stand balanced precariously atop an unsteady grave marker while he takes his half of the gold and rides away. As Tuco screams for mercy, Blondie returns into sight, and severs the rope with a rifle shot (just like old times), leaving Tuco alive to furiously curse him while he disappears over the horizon.

Like all Sergio Leone Westerns, the central theme of this film is greed. Leone loves American Westerns, but hates American capitalism, or rather i think he hates the politics and ideology represented in the traditional Hollywood Western- which leans towards portraying the nobility of ‘manifest destiny,’ and capitalism is a major part of it. Leone’s main design for these Westerns were to subvert and overturn every image, icon, idea and trope associated with the American Western, so i suppose bringing the factor of ‘greed in the old-west’ to center stage in these films- the first two films even has ‘Dollars’ in its title and the trilogy is called ‘Dollars’ trilogy- is part of that game plan. These films comes smack in the middle of John Huston’s “The Treasure of Sierra Madre” made in the Post-WWII 1940s- basically the first Western to show prospectors going mad and becoming murderous in pursuit of gold- and Oliver Stone’s “Wall Street” released amidst the excesses of Reagan-era 1980s- which proclaimed that “Greed is good.” Right from the opening scene where we see three bounty hunters crashing into a tavern to capture Tuco to collect the bounty on his head- man’s hunger for wealth is on full display. Take the basic setup of the film: three confederate soldiers steal gold from their own army and then end up killing each other for it- an almost blasphemous concept as far as portrayal of Civil war in American films are concerned, where the Civil war soldiers are always portrayed as nothing less than steadfast to their ‘honorable cause,’ irrespective of whether they’re blue or gray. Of course, one could write a book on the subversive depiction of the American civil war in the film- at every turn, the war is referred to as useless, needless and human beings being unnecessarily wasted; not to mention the brutal depiction of cruelty inflicted on POWs in prison camps by Union soldiers, and the random shooting of Confederate soldiers branded as spies.

Now coming to other regular Leone themes, like the depiction of religion and family, it’s very much pronounced in this film. Leone loved biblical epics almost as much as he loved westerns- he had worked second unit for “Quo Vadis” and “Ben-Hur”, and one can feel the influence of those epics in images of large groups of people traversing an overwhelming desert landscape, as well as in the choir music that dominates the soundtrack. The images of Tuco force-marching Blondie through the blistering desert brings back images of Moses walking through the desert after being exiled from Egypt by Ramses, or Judah Ben-Hur being taken to the galleys after being betrayed by his friend. The good, the bad and the Ugly are obviously metaphors for angel, devil and man. And therefore, the only one with any inner life, human frailties, a family backstory and emotional beats is Tuco- the most poignant moment in the film is a ‘Cain’ and ‘Abel’ type meeting between Tuco and his priest brother, Pablo, that takes place in a broken down monastery filled with religious icons. On the other hand, we get to know nothing about Blondie and Angel Eyes: they seems to be blessed with supernatural powers that enable them to appear and disappear at will. Take their introduction scenes: Angel eyes suddenly appears out of the horizon as a small dot, then his image grows and grows until it fully fills the screen. Blondie’s introduction is even more iconic and metaphysical: he seems to be hiding behind the camera all the time, and when time comes to save Tuco, he nonchalantly walks into the frame. Though Blondie is called “the good”, he’s good only in relation to the other two, hence all his scenes are either with Tuco or Angel Eyes. He doesn’t have any scenes of his own. And it’s also interesting to note that the caption “the good” appears on his freeze frame in a scene when he abandons Tuco in the desert and steals his money. That’s a very ironic moment and presents a cynical view of the Catholic faith- The ‘Angel of god’ is a flawed character, and also the most unpredictable; though he endures torture (from Tuco)- as all great prophets from Moses to Jesus has done- he also lies and double crosses Tuco at every turn. But he’s also the only one capable of acts of compassion in the film: giving a dying soldier a cigar, or feeling regret for all the soldiers needlessly perishing in the war. In the climax, we see Blondie testing Tuco, like god tests man, by placing sacks of gold in front of him while he’s hanging from a rope. Tuco somehow survives the test, and Blondie once again saves him by shooting and severing the rope. And Tuco, ‘the man’ ever blinded by greed and hatred, is back to cursing his ‘protecting angel.’

This film was Leone’s most stylized, most entertaining and grandest up to that time, and it remains the most entertaining film he has ever made. All Leone films are ultimately about cinema and art of filmmaking. He somehow manages to convey to the audience the sheer joy he feels in making his movies. It’s no wonder that a cinephile like Quentin Tarantino is a hardcore Leone fan, and considers this film to be the greatest directed film of all time. Leone’s films are filled with innovative visual techniques and bravura set-pieces. His trademark visual style of interspersing extreme widescreen long shots of landscapes with extreme close-ups of sweaty, scarred faces is taken to another level here. The film starts with a long, wide shot of a jagged, infertile valley & mountainside. Suddenly, a cowboy’s stubbly face swings into the frame and fills it completely; which means that what was an extremely wide shot of a natural landscape has now morphed into an extreme tight close-up of a human face- and that too without the camera moving an inch and without a single editing cut or a dissolve. It’s truly the magic of movies on display here, and Leone manages to extend this magical quality to each and every frame in the film. Leone was a cinephile himself, and he was inspired by several great directors. We find the influences of John Ford in his shot compositions; of Sergei Eisenstein in his editing; and of Akira Kurosawa in the film’s pacing, but ultimately the final product is Leone’s own. The climactic three-way-duel between the three principals is truly the most iconic sequence in movie history: a masterclass on how to build tension and suspense using editing and music. The great Ennio Morricone, Leone’s regular composer, has written one of the most popular and recognized themes for this film. His music complements Leone’s filmmaking to such an extend that it’s impossible to separate one from another. Apart from the three-way shootout, there’s ‘ecstasy of gold’ theme which plays over Tuco’s delirious search for Arch Stanton’s grave. Then there are three separate themes he composed for each of the principals keeping with their character- Blondie is cool, Tuco is humorous, while Angel Eyes is chilling. The cinematography of Tonino Delli Colli, and set & costume design by Carlo Simi, imparts that unique surreal, post-apocalyptic, never-never-land quality to the film’s visuals that all Leone Westerns are famous for.