No relationship demonstrates the power of a prolific director-actor pair more than John Ford and John Wayne. Together, they made 14 feature films, most of which were Westerns, but each grappled with American mythos. Unfairly maligned as superficially jingoistic, Ford and Wayne poignantly reflected on the nation’s history and its uncompromising implications on its future. Not only do the pair embody the power and beauty of cinema, but they are symbolic of America and its complicated ideas and history. Just because they were brilliant collaborators doesn’t mean they were always cordial. Ford, notorious for his temperamental behavior on set, never shied away from viciously insulting his hotshot movie star. In one instance, during the filming of They Were Expendable, a World War II film that hit home for its veteran director, their relationship was pushed to the test when Ford’s rabble-rousing caused The Duke to crack.

John Ford’s Roughneck Persona and Veteran Background Contrasts With His Sentimental Films

At the prime of his career, with classics such as Young Mr. Lincoln, The Grapes of Wrath, and the Best Picture-winning How Green Was My Valley under his belt, John Ford put filmmaking aside to serve in the United States Navy during World War II. As a Lieutenant Commander and Captain, Ford was a decorated naval officer. He was honored with the Purple Heart Medal for wounds received off Midway Island in June 1942. Ford’s service to his country was captured in his documentary, The Battle of Midway. They Were Expendable, his first postwar narrative film, the director was credited as “John Ford Captain U.S.N.R.” Throughout his filmography, Ford’s films reflect his life at a respective phase. When he was an avid supporter of unions and liberal-minded politics in the late 1930s, he made The Grapes of Wrath.

When Peter Bogdanovich asked Ford how he shot a particular scene in Three Bad Men, he dryly responded, “With a camera.” Seldom participating in interviews throughout his career, Ford was reticent to validate filmmaking as an art form, and approached the subject like blue-collar labor. This gruff attitude toward filmmaking starkly contrasts with the images that Ford crafted on the screen, which were consistently poetic and painterly. My Darling Clementine and The Quiet Man could only be made by a sentimental artist, so much so that contemporary viewers may even be weary of the saccharine quality of Ford’s masterpieces. Despite the romantic undertones of his films, Ford, an Irish immigrant, expressed a hard-nosed edge in the public, which especially manifested during the production of his films. Ford was often harsh to his actors and crew members, with biographer Joseph McBride ascribing him as a “tyrant.”

John Ford Caused John Wayne to Walk Off the Set of ‘They Were Expendable’

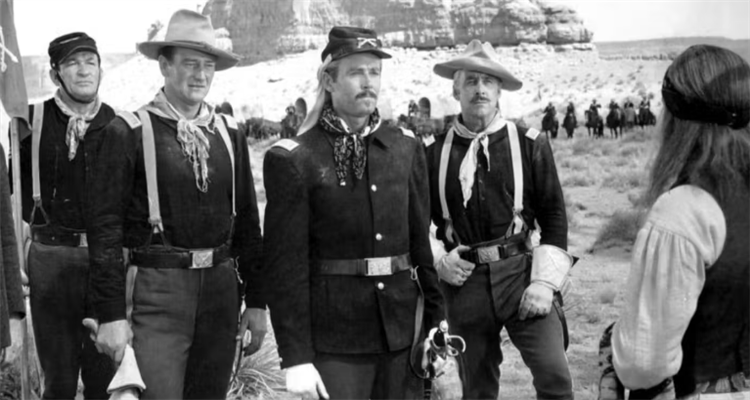

Say what you want about Ford’s notoriously cantankerous behavior, he wasn’t afraid to punch up. Ford mercilessly disparaged John Wayne’s acting abilities, from the way he walked to his speech patterns, once even calling him an “idiot.” From their first collaboration in 1939, Stagecoach, to their last in 1963, Donovan’s Reef, they were consistently contentious, yet always reverential. However, while filming They Were Expendable, it appeared as though Ford’s hostility would irreversibly fracture their bond. The 1945 WWII-set drama follows a Navy commander, Lt. John Brickley (Robert Montgomery), and his second-in-command, Lt. “Rusty” Ryan (Wayne), on a PT boat defending the Philippines against a Japanese invasion during the Battle of the Philippines. Beyond their contribution to the film’s production, the Navy’s imprint on They Were Expendable was immeasurable. Its principal figures, Ford, Montgomery, and screenwriter Frank Wead all served in WWII, and their onscreen credits are accompanied by their rank. A reflection of the period, the film, containing a written foreword by General Douglas MacArthur, is unabashedly jingoistic.

One person who could not reasonably indulge in the patriotism emanating from the film was John Wayne, who notoriously never served in World War II. Despite his masculine persona and sanctimonious image as an American hero on the screen, he refused to volunteer for his country. Wayne was quick to degrade films that challenged American principles as “un-American,” but in the eyes of his director, he was the greatest traitor of them all. As evident by the proud display of Navy themes and iconography throughout the film, Ford cared deeply about honoring the troops. According to Wayne, he had never seen Ford as invested in making a film as he was with They Were Expendable. If Wayne wasn’t already feeling alienated by his lack of service among a cast and crew of veterans, then Ford was going to make him feel alienated. In his biography of the director, Searching for John Ford, Joseph McBride wrote, “A mere Hollywood civilian was hopelessly out of place.”

Ford resented Wayne for avoiding military service and vented his frustration through public acts of humiliation. In one scene, Montgomery and Wayne’s characters salute an admiral as he drives away, with their backs facing the camera. After the third take, upon yelling “Cut!”, Ford yelled at Wayne for everyone to hear, shouting, “Duke, can’t you manage a salute that at least looks as though you’ve been in the service?” Montgomery, playing the mediator, later approached Ford and reprimanded him for speaking to another actor in that manner, but his attempt to alleviate the tension was too late, as Wayne walked off the set for the first and only time in his long career.This affected him so deeply that Wayne, the almighty valiant soldier and cowboy, was brought to tears. Ford could only muster a phony apology after being confronted by Montgomery. The stressful atmosphere of the set would escalate when Ford, while filming a battle sequence, stepped backward and plunged to the floor, and suffered a fracture of his right shinbone. Montgomery filled in as director for the incapacitated Ford.

Why Didn’t John Wayne Serve in the Military During World War II?Similar to Ford’s juxtaposition as a cranky drill instructor compared to his heartfelt nuance as a storyteller, there is thick irony stemming from Wayne refusing to enlist in the war despite starring in countless war films and being an avatar for American patriotism. Critics and historians have theorized that his decision to stay in Hollywood while his contemporaries, including Henry Fonda and Jimmy Stewart, fought overseas was to cement himself as a prominent movie star. McBride wrote that Wayne opted to capitalize on “the benefits of the box office boom in wartime entertainment.” Republic Pictures, the studio producing many of Wayne’s films, filed deferment requests on the star’s behalf. The Ford biography asserts that Wayne’s guilt over dodging WWII enlistment caused him to take aggressively patriotic and right-wing viewpoints, notably when he led the charge to excommunicate alleged communists in Hollywood during the 1950s.

This blow-up on the set of They Were Expendable potentially could have permanently damaged the symbiotic bond between John Ford and John Wayne, but instead, their artistic partnership was just getting started. Through the next two decades, they made upwards of 10 films together, including undeniable masterpieces in The Searchers and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. Oftentimes, primarily seen in the music world between band members, tension and hostility produce great art. While, for a certain cohort of modern film viewers, Wayne was an unremarkable actor with a shallow interpretation of America, Ford consistently used his image to reflect on American history and folklore. Ultimately, Wayne pretended to play a hero, while Ford embodied one.

They Were Expendable is available to rent on Amazon in the U.S.