“You want me to shoot him in the back?” John Wayne asked director Don Siegel during the filming of the western. The Shootist (1976). Wayne was as stubborn as ever as he worked on his latest completed film. But, Siegel insisted, since Wayne’s character had four other fighters to kill on stage — this was no time for the good stuff.

“I don’t shoot anybody in the back,” Wayne complained.

“Clint Eastwood would have shot him in the back,” Siegel replied, knowing that Eastwood’s name would simply be a provocation for the aging star. Wayne turned yellow with rage and yelled, “I don’t care what that kid does, I don’t shoot people in the back”!

Much has been said about the tension that the two stars had over the years. This wasn’t the first time the two old western men had shot each other. But did they have more in common than previously thought? After all, as Eastwood told Kenneth Turan in 1998, “I grew up watching all the John Ford and Anthony Mann westerns that came out in the 1940s and ’50s. John Wayne, with all those kind of western knights, and Jimmy Stewart.” Wayne was clearly depicted in Eastwood’s take on the genre, regardless of what happened between them.

For a time, however, Eastwood’s darker, more nihilistic Westerns, and their undoubted success, were clearly points of contention for Wayne. And, the tension between the two eventually came to a head, thanks to Eastwood’s second film as director, High Plains Drifters (1973), a very violent fable that was a far cry from Wayne’s more romantic and festive Westerns. For Wayne, this change in tone was almost an affront to past generations.

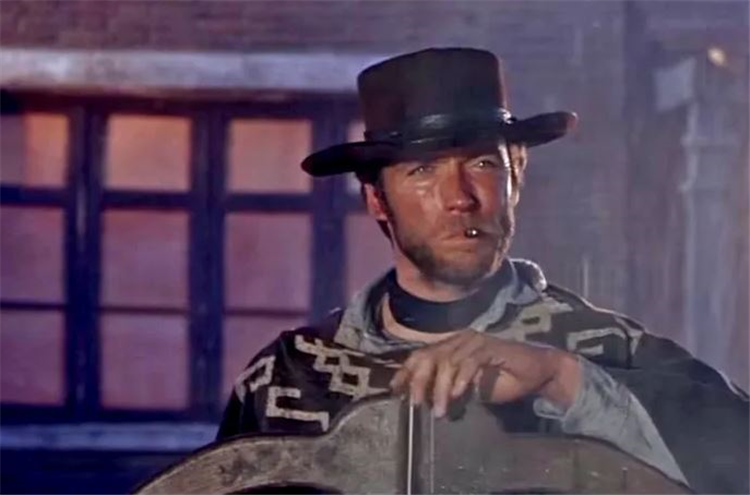

Turning 50 this year, the film High Plains Drifters it was Eastwood’s first western as a director. However, the actor’s rise to fame – which was filled with gunslingers of various moral views, from early TV roles as Rawhide (1959-1965) to Sergio Leone’s brutal Italian classics, such as A Fistful of Dollars (1964) – it wasn’t until the 1970s that Eastwood started directing. And, with the success of his 1971 blockbuster debut thriller, Play Misty for Me, it wasn’t long before Eastwood would challenge himself in the western. However, Eastwood’s film would typify the pessimistic dramatic view of the American Old West era, to the extent that it was more of a supernatural horror film than a classic gunplay tale.

With a screenplay by Ernest Tidyman – famous for his Academy Award-winning screenplay for The French Connection (1971), directed by William Friedkin – High Plains Drifters reflected a more modern approach to the genre, both in tone and content. It follows an unidentified stranger (Eastwood) – who may actually be a ghost – as he enters the town of Lago in search of revenge for a US marshal who was flogged to death while the town held a vigil. .

The atmosphere of the film is dark and tense, the violence is unforgivable and the sense of honor in the straw. Within the first 10 minutes, the stranger has tricked three men into killing them while attacking a woman. It sums up the tone of the new revisionist westerns perfectly. “I never imagined myself as a guy on a white horse or wearing a white hat on a mighty horse…” Eastwood admitted.

Eastwood’s film echoed the grittier new generation of westerns alongside classics such as McCabe & Mrs Miller by Robert Altman (1971), Little big man of Arthur Penn (1970), as well The Wild Bunch of Sam Peckinpah (1968). These young westerns often took a hopeless approach, dealing with disillusioned figures struggling violently against poverty, the forces of nature, and each other. “High Plains Drifters it was meant to be a story,” Eastwood said, “it wasn’t supposed to be anything about rehabilitating the West.”

The characters in these films were not heroic, but rather liars, deceivers and tricksters; greedy for gold as in The Good, The Bad and The Ugly (1966) of Leone or intoxicated by apostasy as in The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean (1972) by John Huston. They were also more violent films. Gunfire was no longer just a sound and a reaction shot, but often bloody, messy and sometimes behind the back.

Wayne was vocal in his criticism of the new approach. “For me,” he told the magazine Playboy in 1971, “The Wild Bunch it was unpleasant. It would have been a better film without the spilled blood.”

Before the pessimistic new Hollywood of the 1960s, Wayne’s cinema had defined the most heroic representation of the Old West, even when the characters he played were known to be flawed. His epic quest at the center of the film The Searchers (1956) by John Ford, as the fanatical character Ethan Edwards, exemplifies this very formula. “Well, there’s some great stuff in there,” Eastwood told The searchers. “I don’t think it stands, in the sense that there are some characters that I wouldn’t play today.”

However, he could have chosen any of Wayne’s shows from Hollywood’s Golden Age, all of which demonstrated an almost mythic appreciation for the landscape and culture of the Old West. Be like the stubborn and determined shepherd Red River of Howard Hawks (1948) or as the escaped convict helping a group of ragtag men around the country in Stagecoach (1939) by Ford, regardless of their background, Wayne’s characters always found redemption, if only in the eyes of the audience. His intense respect for the classic western form is certainly explained by his often scathing answers when asked about the new approach.

“Do you know any country whose folklore is destroyed?” Wayne said in 1972. legendary cowboy, the American public and the world public want to see him”. Wayne was obviously very unhappy with the changes that were happening in Hollywood and in his beloved genre: changes that he felt Eastwood represented, after the young man mercilessly killed people in Leone’s film, For a Few Dollars More (1965) or Hang ’em Hight of Ted Post (1968).

However, the stars were initially concerned about Dirty Harry (1971) of Siegel than for a western. Wayne claimed he was offered the role of tough cop Harry Callahan before Eastwood took it. Either way, although the odds were that the required physique meant the studio would reject Wayne rather than the other way around, the film’s success undoubtedly made the star feel increasingly out of touch with American cinema. When asked about the reasons for his rejection, he gave two. “The first is that they offered it to Frank Sinatra,” he said. “I don’t like being offered Sinatra rejections. The second reason is that I thought Harry was a rogue cop.” The last reason certainly rings true for Wayne’s honest approach to the character.

Anyway, Dirty Harry further solidified Eastwood’s place at the center of Hollywood. The film was an unprecedented success and ushered in a new era of police thrillers worldwide. Indeed, the success was such that Wayne in later years remained pursuing roles of the style of Dirty Harry-t, with films of the same color as McQ of John Sturges (1974) and Brannigan of Douglas Hickcox (1975).

After the success of High Plains Drifters, Eastwood was on the rise with opportunities for more projects. It took on a Larry Cohen script called The Hostiles, a story about a gambler who wins half a fortune from an older farmer; the two men were forced to work together to fend off the bandits. Eastwood was convinced that Wayne would play the old man while he played the young man. He eagerly sent her the script. Wayne was not impressed and told Eastwood as much in a letter.

Wayne’s problem had nothing to do with The Hostiles or with its content, but what Eastwood himself increasingly represented in that genre, thanks to the film High Plains Drifters. “John Wayne once wrote me a letter saying he didn’t like me High Plains Drifters”, Eastwood admitted. “He said it wasn’t really about the people who pioneered the Western. I realized that they were two different generations and he wouldn’t understand what I was doing.”

Eastwood did not respond to the letter directly, but sent Wayne another revised script in the hope that he would be approached for the project. “That stuff is all they know how to write these days…” Wayne complained. According to his son, Michael Wayne, when the latest version of The Hostiles fell into piles of scripts, his father threw him overboard from the deck of his boat, Wild goose, with the irritated words: “Again this piece of m…”. The project fell through and was not realized until 2009, and even then only as a cheap TV movie saw Eastwood’s involvement.

Of course, history shows that Eastwood was right to stick to his guns, instead of relying on Wayne’s increasingly dated approach to the genre. His career as a director flourished, with a string of classics such as The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976) Pale Rider (1985) and his 1992 revisionist western, Unforgiven, which was the last genre film to win a Best Picture Oscar. Fittingly, Eastwood himself saw it Unforgivenas the final chapter in revisionist westerns. “If I were to make one last western,” he said, “it would be because it kind of sums up what I’m feeling. Maybe that’s why I didn’t do it right away. I enjoyed it as the last film of that genre, maybe as the last film of that kind for me.”

At the time, Eastwood was the oldest man of screen westerns, not Wayne. But like Wayne before him, he had some political questions about where the genre was going. For the 1990 Kevin Costner film, Dancing with Wolves, Eastwood’s criticism could easily have been uttered by Wayne in his discussions of the revisionist western of the 1960’s and 70’s. “He was kind of the contemporary guy from the West who was interested in ecology and women’s rights and Indian rights,” Eastwood said. “If you did it the way it was, people probably didn’t get tired of it back in the day, but maybe that’s what’s needed to drive the new generation of moviegoers.”

Despite the big changes and successful legacy of the darker westerns of the 1970s, Wayne still didn’t want to shoot people in the back. Siegel was good friends with Eastwood, so the actor naturally visited the set of the film The Shootist. According to Ron Howard, who also starred in the film, the two actors finally met, and unlike many stories about disagreements and rivalries, they had a good time. There’s still a photo of them smiling and laughing on set: the most famous gun duo in movie history finally putting down their guns, if only briefly. /Telegraph/